Hey there!

I was suddenly tempted while looking at the breads in a local bakery to make my own sourdough as opposed to their citric acid flavored ones. I found an old thread in this forum here that I followed, mostly. I've got wheat berries so I ground them into flour but by day 3 nothing was happening. Then I realized that since my wheat was vacuum packed there probably weren't any live yeast on it!

So, off to the market for some fresh blueberries! The whitish stuff on them, among other things, is wild yeast. I took my blueberries and swirled them around in 1/4 cup water and added that to the starter. Three days in and it's working!

The smell is totally sour, like sourdough, and it's bubbling right along. Can't wait! Per the article I started with I think I'll give it a week before I use it and then put it in the 'frig and keep it as my mother batch.

The blueberries:

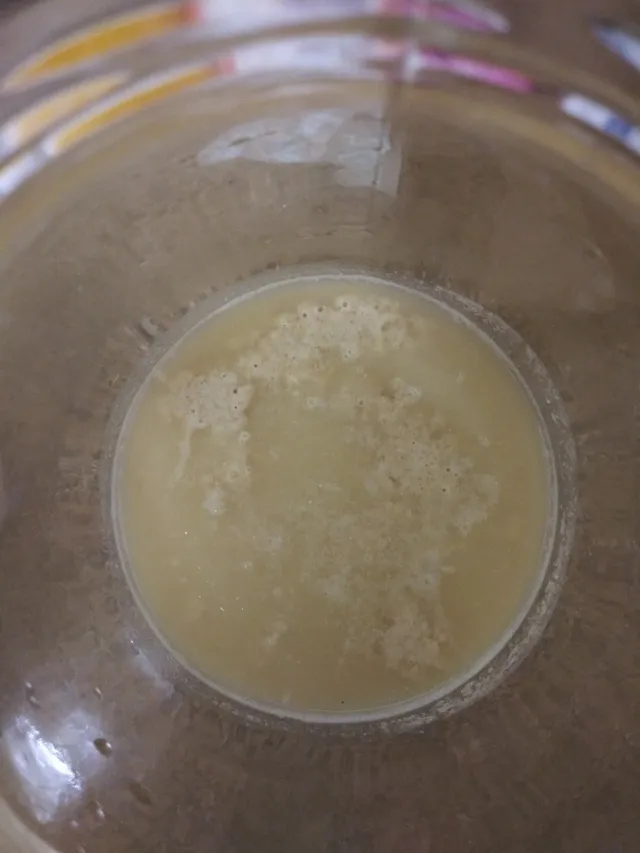

The starter after 3 days with the blueberry water!

Totally stoked!

Thank you all and any input on keeping this alive is appreciated.

Barrie H.

I had no idea the white stuff on blueberries was wild yeast! Very interesting.

I would suggest giving your starter more than a weeks' worth of feedings before you start using it in loaves. You really want the starter to be very active and rise and fall in a predictable manner (this means the colonies of bacteria a yeast in your starter have stabilized to your environment and the flour's you are feeding it). I gave my first starter just over a week and had disappointing results. The second one I got going I made sure to feed until It was doing something predictable and the results were great.

That being said, others have had great results with very young starters and there is always something to be learnt from making a loaf of sourdough so ignore what I said and go nuts! Looking forward to see your first loaf.

When you talk about a stabilized starter, what should we aim ? Is doubling (or more) in 8h to 12h after each feeding enough ? Should it reach peak quicker/slower ?

The time it takes to 'peak' in growth depends on many factors including:

-Temperature of the environment the starter is in.

-The flour used (fresher flour ferments more quickly than old four. whole grains ferment more quickly than white etc..)

- How much mature starter you used as a 'seed' when feeding.

A 8-12 hour time between feedings is pretty standard, but again by tweaking different variables you can adjust this to an interval of time that works for you.

When I say a stable/predictable starter, I mean that the starter, when all variables (temp, flour, etc) held constant, rises and deflates the same every time, taking the same amount of time.

Essentially YOUR starter should be familiar to YOU. You should know what it is gonna do once you feed it.

Thanks for your answer !

Yes, and the same is true of the stuff on plums! Thank you for the posting. I'll shoot for the predictable rise as you mentioned.

Thanks again!

First loaf! The hydration was WAY to high at 75%. This was more like a thick batter than a dough but oh well; the flavor needs more development and the crumb wasn't as large as I'd like. I let it autolyse overnight so the loaf was chewy and I like chewy bread so I've got a plus on my score sheet there!

Thank you!,

Barrie

A note on this - yes the coating on fresh berries is yeast, and it will raise bread (my comment when I did this with backyard blackberries years ago was - man, this stuff will raise the dead). But, at first, the starter is predominantly yeast. It'll take time to get the balanced of yeast and lab, just like a regular starter. The sour smell is probably just fermented sugars, but don't get rid of it, keep going with it. It'll take a little time to lose the berry taste anyway. Enjoy!

I'm seeing patience is the key here. I'll keep nurturing it along; I'm sure it's going to make outstanding loaves.

Thank you.

I always believed this to be a protective coating. Keeps the moisture in and prevents the skin from degrading. Its not very yeasty! Yeast is destructive, not protective.

But yes, I hear the yeast is apparently inside the skins. You can wash off the white coating with no detriment to your fruit based yeasts and in some cases you probably should.

I always thought the yeast lived in the coating. There is a similar coating on grapes and apples and other fruits, as well, which I've also seen it said that the coating is yeast, but I agree with you that it's not like the layer is pure yeast.

It was explained to me once (I think at a winery but not very sure of that) that the coating is generated by the plant as a protective layer, and also a good home for yeast. Yeast colonies grow in the coating, getting there the same way they get everywhere else, I would guess. Then once the fruit has fallen to the ground, the yeast are part of what helps it decompose and make rich soil for the seed to sprout in. So in this case, the yeast's destructive power is actually beneficial to the plant's ability to reproduce.

I'd love to know for sure, if you happen to have a reference. Altho the difference between yeast living in the coating or in the skin is probably irrelevant for sourdough purposes.

There's also a debate that I've seen both sides of regarding whether the yeasts that live on/in the skins of these fruits are even the right type of yeasts for our sourdough starters. I wouldn't mind a reference for that, either, if you happen to have that.

Hi LittleGirlBlue,

I don't have hard link for any of that. I recall that yeast being on the skins of fruit I read somewhere years ago. Prior to posting this reply a quick Google search on "where is wild yeast" turned up results indicated that it's basically -everywhere-. There is more than one type of yeast so it's probably a coin toss as to what you'll find on the fruit!

I get that initiating starters with pineapple or orange juice, i.e. low pH, promotes the growth of the kind we want to make sourdough. A fair test would be to start a batch with water and another with the juice and, under the same conditions, see which one grows what at the end of the day.

The white coating is definitely produced by the plant so is not yeast. It actually has a chemical name, not just a tag like 'bloom'. I find it hard to believe that yeast survives enough on the surface of dried fruit after industrial cleaning and processed drying. To this effect I always presumed the yeast to exist on the inside and we bust it out with physical force and dissolve it in water. My idea was always supported by the observation that when making raisin water, the CO2 immediately emerges from the centres of even skinless fruit. The sugars in the fruit provide the food, as natural intended.

We dont go round scraping skins for yeast...

We provide additives to condition the environment to let the varieties we want, thrive. For example, adding honey suppresses the Brewers yeast that can also result from this process.

The yeasts are not part of any plant structure, including the fruit. They are not released from the plant cells because they do not exist in the plant cells.

Yeasts are single-cell organisms. They grow on the outer surface of whatever they've been deposited on, assuming that they land in a hospitable environment. Some varieties are more at home on fruits, some on grains, and others in totally different environments.

Please take the time to read reliable sources and learn how things work. There is enough misinformation propagated on the Web already. One of the great things about TFL is that there are so many knowledgeable people who generously share what they have learned. That goes a long way toward dispelling myths and misunderstandings.

Paul

Yes, youre right, Ive had biological autolysis floating in my head for 2 days and Im crossing ideas. Ill correct it in a way that still makes my point. I feel you should have offered up some scientific reference to support your point, given the way you followed up your argument. "Read stuff" doesnt fulfil the picture you painted if you are to be one of these helpful people you describe.

Edited!

Hello all,

So, whatever the white stuff is on the fruit skin and wherever it comes from I'm fortunate that it had the flora in it to start growing what at this point REALLY smells like sourdough. Wikipedia has many articles referencing yeast, sourdough, sub-species of the organisms involved, etc.

Good news!

It would be fair to say that all exposed surfaces of plant material, including grapes skins are teaming with microbes; yeasts, fungi, moulds, bacteria, all waiting for their chance.

The whitish bloom found on grapes is a waxy coating composed of fatty acids that helps to repel water and reflect light. See hear: Epicuticular wax

Barata, A., Malfeito-Ferreira, M. and Loureiro, V., 2012. The microbial ecology of wine grape berries. International journal of food microbiology, 153(3), pp.243-259.

Sabate, J., Cano, J., Esteve-Zarzoso, B. and Guillamón, J.M., 2002. Isolation and identification of yeasts associated with vineyard and winery by RFLP analysis of ribosomal genes and mitochondrial DNA. Microbiological research, 157(4), pp.267-274.

Thank you mwilson! ?

Thanks mwilson :)

ooh! references! thank you!