Wheat: Red vs White; Spring vs Winter

Home millers have definite preferences when it comes to wheat. Many favor hard spring wheat over winter wheat for it's somewhat higher protein value (and stronger gluten). Furthermore, some prefer the red variety for it's robust flavor while others prefer the milder taste of white.

Some Background: Hard Red Wheat vs Hard White WheatHard white wheat was developed from hard red wheat by eliminating the genes for bran color while preserving other desireable characteristics of red wheat. Depending on variety, red wheat has from one to three genes that give the bran its red cast; in contrast, white wheat has no major genes for bran color. The elimination of these genes results in fewer phenolic compounds and tannins in the bran, significantly reducing the bitter taste that some people experience in flour milled from red wheat. Nutritional composition is the same for red and white wheat.

Spring wheat is planted in April to May, makes a continuous growth and is harvested in August to early September. Winter wheat is planted in the fall. It makes a partial growth, becomes dormant during the cold winter months, resumes growth as the weather warms and is harvested in the early summer (June and July).

Flour from hard red winter wheat is often preferred for artisan breads.

Artisan bread flour, which is milled from hard red winter wheat, resembles French bread flour in its characteristics, that is, it is relatively low in protein (11.5–12.5 percent). The low protein content provides for a crisper crust and a crumb with desirable irregular holes...Artisan bread flour often has a slightly higher ash content than patent flour. This creates a grayish cast on the flour and is thought to improve yeast fermentation and flavor. (source: How Baking Works by Paula I. Figoni)

This photo shows hard red wheat on the left and hard white wheat on the right

(I don't find the color contrast as marked as in this photo, so be sure to keep your grains clearly labeled.)

The Test

I wanted to see if the slightly higher protein of spring wheat made a signficant difference in gluten development and rising power. A secondary interest was whether there was a marked difference in taste between white and red wheat.

I decided to do a two pronged test of home milled wheat flour: red vs. white wheat and winter vs. spring wheat. I used my tried-'n-true recipe for a fifty percent whole wheat loaf bread. I made the bread four times - twice with home-milled hard red winter wheat and twice with home-milled hard white spring wheat. The baker's percentage was the same for all trials, as were the other ingredients and the procedure followed.

Here are few recipe details...

- The dough is leavened with instant dry yeast.

- The recipe uses a biga, which constitutes about 30% of the dough.

- Flour is 50% home-milled whole wheat flour, 50% commercial (white) unbleached bread flour (including bread flour in biga)

- total hydration (including water in the biga) is 68%.

- The recipe includes a small amount of oil (3%) and buckwheat honey (4%) in addition to flour, water, salt and yeast

- Wheat is milled very fine with a Nutrimill. Flour is used within a few hours of milling.

Fresh Milled Four

I get an equally fine flour from winter and spring hard wheat using my Nutrimill grain mill. As expected, red wheat is more tan than white wheat, though the real life difference is somewhat more obvious than the photo below shows. Bran flecks tend to concentrate in the center of the flour receptacle, which accounts for the darker color in that area.

Final Dough

By the time the final dough is ready for bulk fermentation, the color differences have become more apparent. Since the wheat is finely milled, the bran pretty much disappears into the dough. I made no adjustments in water content for the two different grain flours and could find little difference in water absorption, feel or gluten development. All doughs passed the windowpane test.

Baking

For all trials the dough was baked in loaf pans in a 350F oven using the cold start / no preheat method. Total baking time was same same for both kinds of whole wheat flours. There was no difference in oven spring; all loaves rose about one inch during the bake. The photos below show the loaves at the start of baking and after about 15 minutes in the oven.

The Final Product

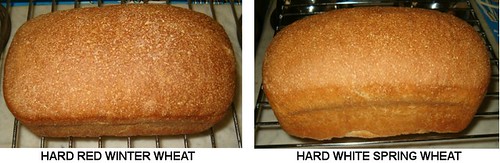

Doesn't look much different on the outside, does it?

Only way to tell the difference is to cut it. Crumb is virtually identical. The red wheat looks like what most of us think of when we think of whole wheat bread. The white wheat looks a lot more like 100% white bread.

Evaluation

I should have believed the North Dakota Wheat Commission. Their brochure on hard white wheat says...

Before I started this test, I'd never worked with hard white wheat. While others frequently comment on it's mild taste, I wasn't prepared for a fifty percent whole grain bread that tasted like - ummmm - white bread! OK, not exactly like white bread, maybe an eensy bit denser and an eensy bit more taste but close enough to make me question the wisdom of purchasing 25 pounds of hard white spring wheat.

A lot of posters here use only whole grain flour, mixing white and red wheats to get the flavor profile they prefer. When they describe white whole grain as mild, you'd better believe it.

Great post! I love when someone goes through experimentation like this and post pics etc. for us all to enjoy.

Now I wonder what "brand" of wheat that is commonly grown here in northern europe. I find the bran to be somewhat in between the two loaves pictured above.

Thanks for the test and report. Several things surprised me.

a. You found no difference in mill between winter and spring. Others have said that the harder spring wheat will give a coarser mill under the same milling conditions.

b. You found no difference in absorption between winter and spring. Others have found that the higher level of protein and damaged starch in spring wheat makes it more absorbent.

c. You found no difference in rise, where others have gotten more rise with higher-gluten wheat.

Maybe differences would have become apparent if your bread had been 100% whole wheat.

You seem to be adding your voice to those who find red wheat more flavorful than white. I think the type of bread would make one more preferable. The bigger flavor issue is that those without home mills are almost always getting old, poor-tasting, whole wheat flour in the store.

I’m also interested in why experts think artisan flour can’t be spring wheat. I’ve been thinking that it’s partly related to the higher absorbance. The water is later released after the action of protease and amylase, which would be inconvenient to the baker.

I’m a home mill novice. In buying grain, I’m wondering how much quality variation there is by year and by supplier.

cbThanks for your post. I do hope that members of TFL will post to this thread so that we can, collectively, explore the differences in wheat grains that are *home milled* into flour.

At this time, I'm not going to respond to the questions you labeled as A B or C. Each one deseves a well thought out response from me (and other readers). I promise to do so in the future.

I would like to respond to other issues you raised in your post...

[quote=charbono on April 23, 2008]Maybe differences would have become apparent if your bread had been 100% whole wheat[/quote]

You're 100% correct. I found the *taste* difference between home-milled hard *red* wheat and hard *white* wheat to be signficantly different. Hard white wheat (available in [i]spring[/i] and [i]winter[/i] plantings) clearly has a more neutral taste.

My test recipe uses 50% commercially milled unbleached white bread flour, which is milled from the endosperm of the grain. The endosperm (generally milled from hard *red* wheat) is largely neutral in taste and the recipe uses well known techniques such as the inclusion of a prefrement - in this case a biga - and an overnight refrigerater rise to develop flavor.

If I had used a recipe that was 100% whole grain (home milled) hard *red* wheat vs. 100% whole grain (home milled) hard *white* wheat I believe the flavor difference would have been even more pronounced. A bread made from 100% whole grain wheat flour would also, at a minium, require adjustments in the hydration (water content) of the loaf.

[quote=charbono on April 23, 2008]The bigger flavor issue is that those without home mills are almost always getting old, poor-tasting, whole wheat flour in the store[/quote]

Absolutely agree. There are certainly excellent commercial sources for whole grain flour in the USA (King Arthur; Bobs Red Mill) *however* we lowly home bakers have no idea how much time has elapsed between the packaging of the flour at the mill and the point in time when we pay for our bag of flour at the supermarket. Freshness of whole grain flour is paramount for flavor (and other properties) and I do believe that those who wish to bake with whole grain flour are best served by milling whole grain at home.

I was curious where you buy your grain from and do they have organic?

a. You found no difference in mill between winter and spring. Others have said that the harder spring wheat will give a coarser mill under the same milling conditions.

b . You found no difference in absorption between winter and spring. Others have found that the higher level of protein and damaged starch in spring wheat makes it more absorbent.

c. You found no difference in rise, where others have gotten more rise with higher-gluten wheat. [/quote]

My thoughts on "c" are in my reply to Rosalie. On to "a" and "b"

[b]A - no difference in milling between winter and spring[/b]

I'm using a Nutrimill grain mill. The benefit (and limitation) of these micronizer mills is that they produce a finely milled flour. Both grains were milled on high speed on the finest setting (the lower dial pointing to the "N" in "Finer"). Winter wheat is slightly softer than spring, which you can test yourself by chewing a few grains of each. But once they've gone through the micronizer mill, the flour fineness is very similar.

If you're not using a micronizer mill, then differences in milling properties would be more apparent. The best way for a home baker to learn about the different milling properties is to use a manual grain mill; most manual grain mills use a fixed groved plate and an adjustable groved plate to crush the grain (not that different in principle from the wind and water powered grain mills people used up through the 1800s). However, a quality manual mill is expensive and I think most prefer an electric micronizer mill for it's convenience and the fine flour it can produce with no effort and in very little time. Cheaper manual mills may not be good at producing fine flour; grain milling attachments (to the Bosch or KitchenAid) have the same limitation.

[b]B - no difference in water absorption between winter and spring[/b]

For testing purposes, I resisted the temptation to make fine adjustments in the amount of liquid during the kneading process (FYI, I measure by weight, not volume). I was a little surprised that there was no appreciable difference in the rise. Do remember, however, that the recipe uses 50% white bread flour also.

I emphasize again the fineness of my whole wheat flour. The bran particles are very fine so they absorb water more readily than a coarser milled wheat flour. The recipe also employs a two hour autolyse for the whole wheat flour and water before the other ingredients are added so both whole wheat flours (hard red winter and hard spring white) have plenty of time to hydrate.

[b]B - higher level of damaged starch in spring wheat[/b]

I honestly don't know if winter wheat has, on average, less damaged starch than spring wheat.

Damaged starch is primarily caused by rain shortly before the grain is ready to harvest. The seed may start to sprout, which increases the amount of alpha-amylase and other enzymes that break down starch. Starch damage in wheat is measured by a test called the "falling number" - values of 300 or higher indicate low enzyme activity and wheat that meets this criterion is preferred for bread flour. Wheat with a falling value of 250 or below may be rejected for milling into flour for baked goods. However, alpha-amylase is not all bad; a small amount is added to many commerical brands of white flour (bread or all purpose) by the addition of malted barley flour because it improves the extensibility of bread dough (the ability of the gluten web to expand to trap the carbon dixode given off by yeast and to stretch during the initial bake at high tempertures - aka oven spring).

A large commercial mill blends flour from different wheats to achieve different grades of flour that meet different specifications. Some well established large scale bakers are known to work with selected mills to get precisely the type of flour they require. When it comes to the home baker, the best most of us can do is read the technical specifications for different flour brands or, if buying grain, purchase it from a reliable and well known source. If you know where your wheat was grown and what year it was harvested you can always check out the weather in that region. The sites of university and college agricultural extension services are a good source for information in different geographical areas, especially the states that produce most of our wheat.

You may also be thinking of Mike Avery's discussion of grain mills for the home user in this TFL thread [url=http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/3793/kernals-or-berries]kernals or berries?[/url] when he says [quote]micronizers produce more damaged starch than steel or stone wheels.[/quote] Mike knows his stuff and I believe him. I haven't, however, found this to be a problem in wheat flour milled in my Nutrimill. If you're interested in milling experiments, check out bwraith's blog on this site.

[b]I’m also interested in why experts think artisan flour can’t be spring wheat.[/b]

Artisan flour can be spring wheat but it would appear that a flour with a protein content of around 12% is preferred by professional artisan bakers to flours with protein content above this number. Hard winter wheat falls in this category.

Speciality wheat flours (aka artisan flours) often have a higher mineral content because more of the endosperm that lies close to the bran coating is incorporated into the flour. It may include the aleurone layer, which is technically part of the endosperm but, in commerical milling, tends to remain attached to the inner layer of the bran. These outer layers are higher in mineral content than the central part of the endosperm.

=========================

End of discourse. Hope you found some of the information helpful. - SF

SF,

I will respectfully dispute your discourse on starch damage. I have (unfortunately) been spending a lot of time with flour lab tests recently and this kind of stuff is getting burned into my brain.

Falling number measures amylase action. High Falling numbers can be produced by grain sprouting in the field.

Starch damage comes from the milling process. If the grinding process is too extreme, that is the grain is taken from its whole state to a fine grind in too few mill passes, starch damage will result. This is why micronizer mills have a reputation for greater starch damage. Some starch damage is a good thing, but too much can lead to problems in baking.

Hope this helps.

[quote=proth5 on April 24, 2008]Falling number measures amylase action. [u]High Falling numbers[/u] can be produced by grain sprouting in the field.[/quote]

Respectfully submit that, according to my sources, [u]high[/u] falling numbers indicate [u]low[/u] amounts of the starch-degrading enzyme, alpha-amylase, in grain.

See, for example, [url=http://www.udel.edu/FREC/PUBS/ER06-02.pdf]Understanding the Falling Number Wheat Quality Test[/url] and [url=http://www.wheat-research.com.au/media/factsheets/Falling_Number.pdf]WHAT DOES A “FALLING NUMBER” TEST MEAN?[/url]

Thanks for pointing out that starch damage comes from the milling process and that this is distinct from the amount of alpha-amylase in grain.

compulsively yours - SF :)

[quote=foolishpoolish on April 23, 2008 ]Is there a noticeable difference in the bread flour (ie not whole wheat) that you obtained from milling red wheat vs. white wheat? Have you done an all-white loaf comparison?[/quote]

I am totally confused by your question.

My test recipe is 50% whole grain flour (milled from wheat grain with a Nutrimill grain mill which, by defintiion, makes it 100% whole wheat) and 50% commercially milled unbleached white bread flour (which is milled from the endosperm of the wheat and, depending on source, will have varying percentages of protein and mineral content).

I have *not* done an all-white loaf comparison.

If you can better focus your question, I would be happy to answer it.

[quote]My test recipe is 50% whole grain flour (milled from wheat grain with a Nutrimill grain mill which, by defintiion, makes it 100% whole wheat) and 50% commercially milled unbleached white bread flour (which is milled from the endosperm of the wheat and, depending on source, will have varying percentages of protein and mineral content).[/quote]

I didn't see in the original post that you specified commerically milled bread flour. I assumed you had milled the (white) bread flour also.

Thanks for explaining.

Subfuscpersona, you compared hard red winter wheat with hard white spring wheat, varying both color and season. It's theoretically possible that red spring and white winter compared would fare differently. Though, frankly, your post is the first time I've heard anyone talk about the season of white wheat, so maybe there isn't hard white winter wheat.

Anyway, if there is no white winter, maybe you could compare red spring with white spring, varying only the color.

Rosalie

[quote=Rosalie on April 23, 2008]you compared hard red winter wheat with hard white spring wheat, varying both color and season.[/quote]

I did indeed vary two characteristics, and you're right, the better comparison would have been to have hard spring wheat for both the red and white varieties. I do believe there is a winter planting for white wheat (I will check my references and see if I can confirm this). There is [i]soft[/i] white wheat (I ordered some from Wheat Montana but haven't used it yet).

If I remember correctly, I believe you also home mill and prefer hard spring wheat to hard winter wheat.

If the baker wants to make loaves that contain a large amount of other, non-gluten containing ingredients (multi-grain loaves come to mind) and wants a 100% whole grain loaf (or one with only a small amount of white flour) I think hard spring wheat would be the better choice since it's slightly higher protein content could off-set the lower gluten content of the other ingredients. If the baker just wants a 100% whole wheat loaf, then hard winter wheat might do as well as hard spring wheat.

The test has to be taken in context. It does use 50% white flour, which can mask the differences between hard spring vs hard winter wheat. For testing, I wanted to use a recipe that I'd made many times before, so the results wouldn't be thrown off by attempting something new. FYI, I don't make 100% whole grain bread (I've gone up to 70% whole wheat, 30% white unbleached bread flour but I always use some white).

The biggest difference in the test was the taste of white wheat vs red wheat. I don't think that would change. If the baker wants the nutritional qualities of whole wheat flour but dislikes the taste of red, then white wheat is an excellent alternative. (BTW, I have used the hard white spring wheat for egg pasta, where it performed very well.)

Do you have preferences between hard winter vs hard spring wheat? Please share your experience.

SF,

I got a batch of soft white wheat by mistake. It is fairly useless for bread making. I really thought that I had forgotten how to bake when using flour from this wheat. You may wish to use it for pastry applications or blend it with semolina to use for pasta. Baking bread will break your heart.

If I may comment on your experiment, my research indicates that the primary difference between Spring and Winter wheat from a baking application standpoint is that Spring wheat is less able to stand the rigors of free standing hearth baking. Since you produced pan breads, this may also have masked the differences. Spring wheat supposedly has a higher protein content, but Winter wheat supposedly has a higher quality protein. Higher protein content vs higher quality protein - ah, that way madness lies.

But you may want to try a freestanding loaf if you want to display the qualities that are supposed to differ.

Hope this helps.

Thanks for your clarification of why micronizer mills can produce greater startch damage. So we have two potential sources of starch damage - weather conditions prior to harvest and milling techniques. Do you have any information on commercial roller mills and starch damage (just curious)?

WINTER WHEAT and HEARTH BREADS[quote=proth5 on April 24, 2008]my research indicates that the primary difference between Spring and Winter wheat from a baking application standpoint is that Spring wheat is less able to stand the rigors of free standing hearth baking...Since you produced pan breads, this may also have masked the differences. Spring wheat supposedly has a higher protein content, but Winter wheat supposedly has a higher quality protein. Higher protein content vs higher quality protein - ah, that way madness lies.[/quote]

I've also read that winter wheat is better for hearth baking. On the other hand, what, exactly, is "higher quality protein"? Anyway, here's what I remember reading on the topic (no real practical experience to offer) on why hard [i]winter[/i] wheat may be better for hearth breads...

> gluten is better able to withstand long fermentation periods without being degraded by the increase in dough acidity - maybe that's the "higher quality protein" part.

> higher mineral content. The theory is that, since winter wheat is in the ground for a longer period, it takes up more minerals from the soil, which show up in the grain. I have no idea if there are any reputable tests of this theory.

WHITE WHEAT and PASTA DOUGHInteresting that you blended soft white wheat with semolina for pasta dough. I would have thought that the soft white wheat might make the pasta break up during cooking.

I've been using 50% hard spring white wheat and 50% bread flour (12% protein) for egg pasta dough. Since white whole wheat is so mild, the taste of the pasta doesn't fight with the sauces. I'm going to try gradually increasing the percent of home milled hard white wheat in my pasta dough and see how it goes.

Another member here makes her own pasta dough with 100% home milled kamut flour. Said her family loved it.

I have seen several references to "lower absolute protein, but higher quality protein" about several aspects of the wheat berry. I contend "that way madness lies" because I cannot find any definition of protein quality (and I've looked.) The best I can derive is that protein quality means that the particular wheat or part of the wheat seems to display better qualities when baked in a given application.

I've blended low protein flour with semolina to make lovely pasta, so it works for me. I seldom use anything but a blend anymore. It suits how how I make pasta - which is to mix in a food processor, roll it extremely thin, and cook it immediately.

As for starch damage in roller mills, what I can find is that aggressive roller milling - that is setting the rollers too close together early in the milling process - can cause excessive starch damage. So good wheat can be ruined by bad milling. Excessive starch damage can cause problems in free standing loaves because the dough will absorb exta moisture, but release it to become overly slack after proofing. What I have found interesting, however, is that brwraith (who is really the expert on this) had a couple of batches of home milled with what would usually be called excessive starch damage, but the hearth bread was lovely. I am sending a sample of my home milled for testing this week (a small sample, for a few tests, as I mill by hand and I am not getting any younger...) so I shall see my starch damage numbers and think about them vis a vis my baked loaf.

Hope this is helpful.

I think the quality of the protein is a measurement of how much gluten the flour can develop. Durum flour has more protein than standard wheat flour, however it doesnt develop as much gluten as standard wheat.

Might be right, might be wrong..

In some contexts, protein quality refers to how complete the protein is, that is how many of the eight essential amino acids it contains and in what proportion. Is that possibly what it means? That would have nothing to do with bread baking qualities.

Rosalie

The protein in wheat comes in a large part from growing conditions. Our hard red organic spring wheat is 14% protein . We have neighbors that are also organic farmers that grew the same variety of wheat as we did last year but their protein was only 10%. They are within 5 miles from us but their soils are different and their methods are different.

We grow a specialty legume that produces a lot of natural nitrogen per acre and the wheat that we plant on the fields that have had this crop on it the year before always has good protein. We also have good falling numbers. Nitrogen in the soil is key to protein content in the wheat.

As far as grinds go- different varieties of wheats have different properties. Some have a harder bran and grind a bit coarser than other varieties. The same goes for white wheats and also spelt for that matter.

I have found that the red wheats do have a bit more of a great nutty flavor than white wheats do. I think it is all about personal preference.

www.organicwheatproducts.com

[quote=Rosalie on April 23, 2008]...your post is the first time I've heard anyone talk about the season of white wheat, so maybe there isn't hard white winter wheat.[/quote]

hi Rosalie,

I found the reference. There is indeed a hard white [i]winter[/i] wheat, at least in Kansas. Check out this article published by the Kansas State University Agricultural Experiment Station [url=http://www.oznet.ksu.edu/library/crpsl2/srl120.pdf]HARD WHITE WINTER WHEAT FOR KANSAS[/url]

I've no idea how widely it is grown. Even if farmers are growing it, it may be hard to find and I'm not convinced it would be worth the trouble for the home baker.

Its interesting (possibly) to note that the US government does not distinguish between winter and spring hard white wheat in it's Wheat Classification System (though it does distinguish between winter and spring hard red wheat). See [url=http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/4762/major-wheat-classifications-usa-reference] Major Wheat Classifications - USA reference[/url]

Damaged starch happens during milling and is determined by two things: the hardness of the kernel and the milling techniques. It’s important in baking because it increases absorbance and enables amylase activity. Spring wheat is generally harder than winter wheat, and a little more damaged starch is usually found in its flour. Hard spring wheat is also generally higher in protein than hard winter wheat, with protein being quite absorbent. Thus there are two reasons for spring wheat’s higher absorbance. Of course, the bran of both wheats requires extra water.

Some say that spring wheat’s gluten is of lower quality than winter wheat. Research indicates that gluten quality may be determined by the ratio of gliadin to glutenin and the ratio of high-molecular-weight glutenin to low-molecular-weight glutenin.

I am hoping that you will repeat the test with at least 75% whole wheat, a higher hydration for both loaves, and a little more water for the spring wheat.

Maybe you’ll like the taste of 75% white whole wheat better than 50%.

cb

I love useing K.A. new Organic White Whole Wheat for my muffins and scones,cookies ...it is a blend of both the Hard white winter and the Spring White Wheats. The White Whole Wheat is Hard White Spring.

Sylvia

I would love for some of our food scientists to weigh in on this. This seems like a good topic for Emily Buehler, author of "Bread Science".

I am particularly interested because of a recent experience with home milled kamut flour when I ran out of my hard,red spring wheat beries. Kamut has plenty of gluten but it is very stretchy gluten.My loaves were really flat unless I used pans. On the forum, I was told this is a natural characteristic and that it's not the quantity but the quality of gluten.I had previously only used kamut as a part of my flour.My red,hard,spring wheat always seemed to have plenty of gluten and, in fact, I usually cut it with a lower gluten whole wheat to produce softer WW sandwich bread.

SO what is the explanation for the "difference" in the quality of the gluten between wheat strains?

As a chemist, let me see if I can interpret what Emily Buehler says in her book, with respect to the observation about kamut flour.

Gluten in bread is formed from two different proteins that are present in flour. One of those proteins is responsible for the elasticity of the gluten. The other is responsible for the extensibility of the gluten. If the grain has more of one or the other of those proteins than what is ideal, the flour will make dough that is more rubbery or more runny than the ideal dough.

Several posts mention that too aggressive milling is the cause of excessive damaged starch in the milled grain. That was true even with the old stone millwheels. When grinding grain, those millers had to 'sniff' at the millstones all the time, and back off on the power whenever a burned smell was detected. A good miller was one that could crank up the millwheels almost but not quite to the point of that burning smell, finishing the flour as quickly as possible without damaging it. Hence the phrase "keep your nose to the grindstone".

I've been looking into buying grains in bulk for the first time and this post was REALLY useful! We've been using spelt and kamut for the past year or so. The breads come out delicious but kind of gritty, previously I thought it might be because I grind my grains in a vitamix instead of an actual mill but it seems like it's just the wheat variety. I think I need to find some great quality organic white wheat if I am going to convert my husband.

I would say it's slightly harder than hard spring wheat. So it could be that the vitamix cannot give you a really fine flour from kamut.

I'm glad you found the thread useful. (I'm the original poster). - SF

Following this very informative post, can someone kindly provide a description (including protein content and baking qualities) for each of the wheat varieties below?

Thanks a lot :)