Two years ago Nat purchased Chad Robertson’s Tartine Bread for my birthday and wrote an inscription on the inside cover … ‘To inspire you’ …

When I want to shake things up in my kitchen and try something different this is the book I turn to. I love the restlessness and pursuit of perfection in the stories. For me, this is its inspiration. It is not a manual and it is not a handbook … it’s the story of a journey.

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091145096/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091137795/] [/url]

[/url]

While I have baked many of the formulas in Tartine Bread over the years I have not experimented enough with Chad’s schedule for maintaining a leaven. This was to be part of my inspiration this week so I converted a portion of my firm levain into a 100% hydration starter fed with 50% freshly milled wheat and 50% plain flour.

The trick is, you see, to catch Chad's leaven at the perfect time. I find this is even more critical for me using fresh milled flour and I have on many occasions had to do an intermediate build to save an over-fermented leaven. And the best (and cheapest) tool I have found for judging leaven readiness? … my nose!

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091137293/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091143634/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091143194/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091135939/] [/url]

[/url]

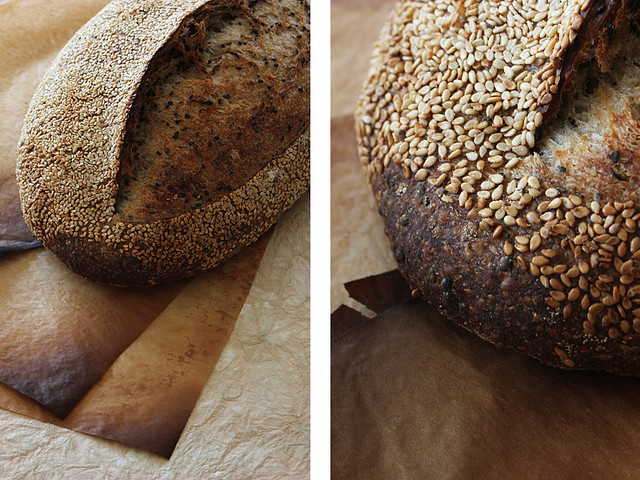

After fermenting in the cool night air the leaven passed both the float and sniff tests (sounds gross) and was then mixed into the dough. Tartine’s sesame loaf uses the basic country bread formula with a cup of toasted unhulled sesame seeds mixed through the dough in the early stages of bulk fermentation.

The slow gentle dough manipulation is relaxing, but I still find it a high maintenance bread to prepare. Keeping temperatures maintained with a small amount of dough over a four period can be tricky during the seasons and the constant attention required for turning the dough can be frustrating. In the end however I was rewarded with subtle dough that shaped easily and bloomed beautifully in a hot oven.

The sesame flavours are subtle. I think Nat was expecting stronger flavours from this bread and was surprised by its sleepy nature. A tablespoon of sesame oil in the dough could be a nice addition without overpowering any of the future flavours that would be stacked on a slice or two.

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091142218/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091134781/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091140784/] [/url]

[/url]

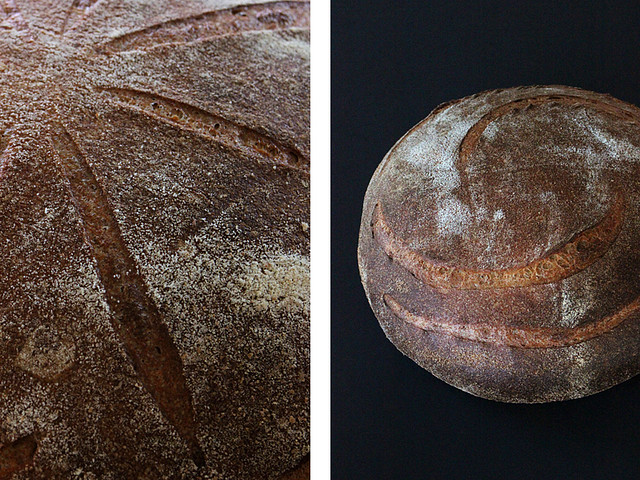

My miche adventures continue …

My experimentation with creating high extraction flour has moved on to the process of tempering. By slowly adding a controlled amount of moisture to grain over a period of time, the bran will toughen allowing easier (and larger) separation when milling. My process of tempering is high-touch. I don’t own a grain moisture meter so I was extremely careful that the grain was dry to touch before milling.

One percent of water a day was added to the grain over a four day period followed by a final 24 hours rest before milling. Normally I mill cold grains from the fridge but have heard that this can lead to the bran shattering into smaller pieces so I instead milled room temperature grains. I feel like I am a bit stuck with this. The small stones on my mill have a tendency to heat up the flour quite substantially but I do end up with larger pieces of bran and softer flour using this process. Hmmm …

The resulting flour was sifted to 80% extraction in one pass and was not re-milled or re-sifted. A more complicated miche was planned for this bake. I would use a rye starter in addition to my standard levain, plus include a small amount of barley malt extract for flavour and colouring only.

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091133493/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091133073/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091139308/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091138884/] [/url]

[/url]

Tempered High Extraction Miche (2 x 2kg miche)

Formula

Overview | Weight | % |

Total dough weight | 4000g |

|

Total flour | 2286g | 100% |

Total water | 1714g | 75% |

Total salt | 43g | 1.8% |

Pre-fermented flour | 571g | 25% |

|

|

|

1. Rye sour – 12 hrs 25°C |

|

|

Starter (Not used in final dough) | 10g | 10% |

Freshly milled coarse rye flour | 55g | 50% |

T130 rye flour | 55g | 50% |

Water | 186g | 160% |

Total | 296g |

|

|

|

|

2. Levain – 5-6hrs 25°C |

|

|

Previous levain build | 174g | 50% |

Flour (I use a flour mix of 70% Organic plain flour, 18% fresh milled sifted wheat, 9% fresh milled sifted spelt and 3% fresh milled sifted rye) | 348g | 100% |

Water | 201g | 58% |

Salt | 3g | 1% |

|

|

|

Final dough. DDT=25°C |

|

|

Rye sour (1.) | 270g | 15% |

Levain (2.) | 722g | 42% |

Sifted fresh milled wheat (80% extraction) | 1715g | 100% |

Barley malt extract | 50g | 3% |

Water | 1267g | 74% |

Salt | 40g | 2% |

Method

- Mix rye sour and leave to ferment for 12 hours at 25°C

- Mix levain and leave to ferment for 5-6 hours at 25°C

- Combine flour and water then mix to shaggy consistency - hold back 100 grams of water.

- Autolyse for one hour.

- Add levain and rye sour to autolyse then knead (french fold) for five mins. Return the dough to a bowl and add salt and remaining 100 grams of water. Squeeze the salt and water through the dough to incorporate (the dough will separate then come back together smoothly). Remove from the bowl and knead a further 10 mins.

- Bulk ferment for two hours with a stretch-and-fold half way through. Mine was ready after 1.5 hours … watch the dough!

- Divide. Preshape. Bench rest 30 mins. Shape into large boules and proof in floured baskets seam side up.

- Final proof was 1-1.5 hours at 25°C

- Bake in a preheated oven at 250°C for 10 mins with steam then reduce temperature to 200°C and bake for a further 40 mins.

One and half hours into a planned bulk ferment of two hours I could tell the dough was ready for division and shaping. Perhaps it was the inclusion of the rye starter, perhaps the malt or perhaps both … either way, the dough was moving fast.

I am becoming braver with both my proofing and handling of these large breads but peeling one into my home oven is still a stressful moment. Our poor little oven does its best to punch it up while I sit and dream of a masonry oven or stone floor deck oven and the results I could achieve.

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091131699/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091131147/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091136808/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091129879/] [/url]

[/url]

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/8091129297/] [/url]

[/url]

The sifting method, malt and rye starter created a darker crumb than previous miche but gave the bread a deep flavour that was nicely balanced. I had suspected the rye starter would have a large impact on the flavour but this was not the case at all.

So will I continue to temper grains before milling? I am really not sure. It creates more planning and logistics before a bake. I do end up with softer flour, but the heat generated by the mill really bothers me. I think some experimenting with tempering and using the fridge to cool the grains before milling may be in order.

Cheers,

Phil

p.s. Happy World Bread Day everyone!

- PiPs's Blog

- Log in or register to post comments

I just have to say you make fantastic bread! How long have you been at this whole bread baking business?

That's so weird that you would ask that :)

I was actually trying to work that out this morning ... It would be about six years. Jim Lahey's no-knead bread and Mark bittman have a lot to answer for :)

cheers,

Phil

As always, simply beautiful work. I'm amazed how clean your station is.

Thanks carblicious,

I do try and keep a clean kitchen ... I have worked hard on my method/technique to create the least amount of mess as possible.

cheers,

Phil

So glad you are inspired ...

Happy baking!

Phil

Phil, your explanations are always crystal clear and precise: watch the signals and search the right clues rather than follow a timeline. Great bread, of course!

Thank nico,

I have a print of René Magritte's painting titled - 'this is not a pipe.' It's to remind me not to be entirely fixated/focussed on the formula only.

In other words, the formula is not the bread. So I watch the dough :)

sure bakes up some fine bread; richly browned, even thick dark crust, open crumb and with some nice lift too. I'm surprised the sour didn't come through more but without a long cold retard it might be restrained. It is nice to see another one of your one day breads (if the rye sour is ready to go) turn out so well.

Nice baking on World Bread Day. It just started here so we have to get some kind of bread in the oven before the day is over :-)

Cheers!

Cheers! Thanks!

A good oven can make such a difference ... A few years ago I was in another rental property with just the worst oven. The only decent bread I could bake were boules in dutch ovens ... and all I wanted to do was to be able to bake a batard ... You can have the nicest dough in the world ruined by an average oven :)

Cheers,

Phil

The miche are glorious, and the sesame breads gorgeous. Your pictures are artfully done, and crystal clear as always.

Nicely done Phill,

Ray

Thanks Ray,

Cheers,

Phil

Especially love the contrasts between white sesame on the crust and black sesame in the crumb. Lovely.

Thanks txfarmer,

The seeds on the crust worked especially well ... I was pretty happy with that :)

Chers,

Phil

David

Thanks so much David,

Cheers,

Phil

miche (but you know that...)

Although a grain moisture meter is a daunting investment, what I have found is that you need to get that moisture to about what the mill will bear and this is a fairly exact science requiring a meter. There are some who advocate testing the grain by biting it. So with this process you would need to learn by trial and error what "bite texture" will produce the best separation.

Frankly, sometimes (sometimes, hah!) time is tight for me and I don't do a good job with tempering to an exact percentage. It shows in the bran. When I hit the sweet spot, the bran has large flakes and is translucent. I look at it and think "Now, there's some nice bran." That's when you know you're a miller - when you think that bran is beautifull.

36-48 hours seems to be the time required - adding moisture over time (if you had a meter - not more than 1% or so per day) seems also to mean something in the process.

Simple things executed perfectly. So many little steps.

Pat

Glad ya like the miche Pat :)

Gee, you are making a pretty convincing argument for a moisture meter ... I wonder if the speed of the stones also makes a difference to what moisture a mill can handle?

Yeah, I was trying the bite method ... but that is going to take a very long time to get any kind of confidence in what I am doing.

That's so funny when you say "Now, there's some nice bran." ... I remember being so excited with the fluffy pieces of bran and poor Nat having to feign interest while I showed her :) ...and I was excited ... normally the komo mill produces a very fine and even flour ... I want those large pieces of bran!!!

I have heard the 'not more than 1% per day' ... but the 36-48 hours ... is that for each addition of moisture or total tempering time?

Cheers,

Phil

A good moisture meter is a big expense. The one I have has different settings for different grains, but does not include grains like triticale or spelt (it does have wheat, rye, corn coffee, and, I think some others). It is a Delmhorst G-7 and financial guru Suze Orman herself not only said that I could afford it, but that I deserved it. It does make a difference in the confidence that you have going in that your moisture level is correct and you won't be gumming up your mill.

Don't know how the speed of the stones figures in to the equation because my mill only turns as fast or as slow as I turn it. An interesting observation came from my young nephew (I had never thought of this before, but for once he is right) that the sound coming from the mill varies not with the speed at which it turns, but with the fineness of the material. Which may indicate that speed is not the biggest factor to consider.

Anyway, the 36-48 hours is total tempering time. One hears stories that many European mills temper very slowly and that this is one of the many differences in their flours. US mills tend to steam temper - which is done in a very short time frame. The advice on longer temper times comes from the millers at Heartland Mills - who do use slow, cold tempering (cold meaning "room temperature"). As with everything, one ponders the balance of time - would it be better to temper over 72 hours? Or more? And is it really something that is even worth it. I sometimes need to do additions of water and then - well, I go to work in another part of the country for a week - and then I do my final addition when I return home and wait 24 hours. I get some nice fluffies when I do that. Hmmmm.

Happy milling!

Pat

mmm ... I have noticed the biggest change in milling sound when I switch from cold grains to room temperature grains. The cold grains give a really high pitched brittle sound .... the room temeprature is a more mellow sound, though you would be hard pressed to convince Nat that it is a mellow sound.

Cheers,

Phil

Beautiful loaves and photography.

I am jealous of your amazing natural lighting you have in your kitchen.

I do not have that option, only to shoot outside or using inside lights which look so artificial compared to your natural light.

Cheers.

ian

Thanks Ian,

I am very lucky with the light we have here ... but there are still days where I have to battle and experiment to get a result I am happy with.

cheers,

Phil

Love that scoring too on your miche!

Phil,

When I saw you had posted again I settled into my chair and sat back knowing I was in for a treat that I wanted to savor. I was not disappointed....No pressure intended :-)

Love your photos as usual especially the ones of the finished sesame loaf. How did you get the sesame seeds on the crust to stay adhered so well? I can only think egg wash.....but even with an egg wash when I make Karin's Simit bread I get sesame seeds that delight is popping off of where I have so painstakingly placed them the first chance they get!

You mentioned your discomforts with Chad's laborious process with this loaf and now I want to know if you feel that the flavor etc that results is worth all that effort or if you feel like you can get the same results using your 'usual' method for making a similar loaf?

Last question because I am slow on some things..... If it isn't a pipe what is it?

Take Care,

Janet

:) ... it's not a pipe ... it's a painting of a pipe.

To be honest ... I really can't say that I get better results using slow stretch-and-folds over a long period. I prefer the method I have been using and feel I get as good a flavour using the firm levain and a better developed dough ... that translucent fine, feathery crumb ... oh, and I love giving dough a nice long 'real' autolyse. His process works but I am fascinated that Gerard's method works equally well ... I notice I am much more discerning about giving dough folds.

The sesame seeds are adhered with just water. I shaped the dough, rolled it on a fairly wet towel then rolled it in the seeds. They didn't budge :)

cheers,

Phil

Once again how easily I can miss the blatantly obvious. I love it :-)

Your findings about certain, specific methods are similar to what I am experiencing. Using freshly ground whole grains is truly very different than using store bought bread/ all purpose flours. Following methods for breads using only those type of flours is not merely the simple - 'just add more water' approach. The flavor does not have to be coaxed out. It is already there but the grains do greatly benefit from a long 'wet time' which effects the texture and makes them more digestible but also adds the factor of too much enzyme action...temp. and timing being much more crucial. (It does help with flavor too. DOn't want to dismiss that. It is just in a much different way.) Issues with gluten development are also different so the kneading process is different too.

I knew this all in 'theory' when I began using my whole grains but now that I have a couple of years under my belt of practical baking experience I am better able to trust what my doughs are telling me. I trust more in the process that I have come to use too because, like you, the end result is pretty much the same.

I prefer a firm leaven too. 60% HL was my usual but I have had to loosen that up - just too firm for my hands to mix 3x's a day every day....I now keep mine between 70% and 75% but adjust the water in the final dough so all equals out in the end. The results are still more or less the same. My doughs still maintain their strength and I get nice volume. My hands are much happier with me :-)

Thanks for your response to my question. Always helps to hear what you have experienced on your end.

Take Care,

Janet

Ahhh, such a lovely blog post! I enjoy the photos and love following your thought process and seeing the results as you explore different breads. Fascinating discussion on tempering, a miche is a favorite style of bread for me and I've been thinking of a food mill, but wondering how one sifts out the bran if it isn't in large flakes. Thanks so much for answering my question :)

Thanks Flourchild,

A miche is a very satisfying bread to bake ... and eat :)

Cheers,

Phil

Hi Phil,

Two very, very beautiful breads, so lovely to see these :^)

The positive/negative contrast of the dark and light sesame seeds, and the speckled crumb of your Tartine bread...

really gorgeous!

I love how the senses play such a big role in baking bread, including the sense of smell - I wanted to please ask

(if it's possible?) to describe the aromas you are looking for in your leaven, to judge its readiness?

Your miche looks just perfect to me, admiring so much the effort going into the milling and the creation of this bread, and wishing you the best as you experiment with techniques to get the bran and flour you are looking for.

Your bread is already the bread of my dreams, but I can relate to dreaming of deck ovens with heat, too...

:^) breadsong

Thanks breadsong :)

Chad probably describes it best in his book ... "Floral, fresh, creamy, silky, sweet, milky" ... You know when you have gone to far ... acidic aromas start getting stronger and become overpowering.

The leaven won't have risen as far as it would of by the end of a full day or normal starter cycle. It should pass the 'float test' and smell as Chad describes. Perhaps one day feed your starter as per his method and notice how the aroma changes during the day.

The milling and sifting is really a lot of work in a home kitchen .... I think the clean up afterwards takes the longest :)

Cheers,

Phil

Thanks breadsong :)

Chad probably describes it best in his book ... "Floral, fresh, creamy, silky, sweet, milky" ... You know when you have gone to far ... acidic aromas start getting stronger and become overpowering.

The leaven won't have risen as far as it would of by the end of a full day or normal starter cycle. It should pass the 'float test' and smell as Chad describes. Perhaps one day feed your starter as per his method and notice how the aroma changes during the day.

The milling and sifting is really a lot of work in a home kitchen .... I think the clean up afterwards takes the longest :)

Cheers,

Phil

Thanks Phil - I should go back and re-read that.

Noticing how the aroma of the levain changes as time passes is helpful advice - usually I only check on the aromas when the levain is peaking.

We had a really nice run of warm weather this summer and fall; I noticed changes in my rye levain, the aroma becoming beautifully fruity, which translated into the flavor of the bread - joy!

:^) breadsong