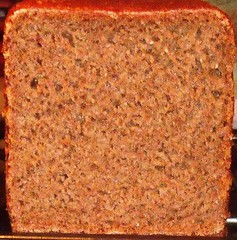

80% Rye with a Rye Soaker, plus Black Strap Molasses

Very close to 2kg weight of paste, baked in a Pullman Pan, resulting in beautiful bitter sweet flavour!

This is close to Jeffrey Hamelman's recipe in "Bread: A Baker's Book of Techniques and Recipes" pp.213-4. The differences I used were as follows:

- Rye Sour is prepared as a liquid culture with water at 1.67 times the flour.

- Molasses in the formula at 4% on flour

- Overall hydration is increased to 85%

- High Gluten flour is substituted with regular Strong White Bread Flour [Allinson, 12% protein]

- There is no added yeast in the final paste.

Impact of relying on the Sour only for leavening meant 40 minutes bulk fermentation, then 2 hours 20 minutes final proof in the Pullman Pan.

Bake profile was 2 hours at 160°C, with a pan of water in the oven.

For more information on this bread, see my earlier postings, here: http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/21307/some-variations-hamelman039s-quot80-sourdough-rye-ryeflour-soakerquot and here: http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/17539/slight-variations-two-more-formulae-hamelman039s-quotbreadquot

Pain au Levain using both a Wheat Levain and a Rye Sourdough

Hamelman (2004) has a similar concept in his book, above, but this formula is quite different in a number of ways. Full details are given below:

|

Material |

Formula [% of flour] |

Recipe [grams] |

|

1. Wheat Levain |

|

|

|

White Bread Flour |

16.67 |

250 |

|

Water |

10 |

150 |

|

TOTAL |

26.67 |

400 |

|

|

|

|

|

2. Rye Sourdough |

|

|

|

Dark Rye Flour |

8 |

120 |

|

Water |

13.33 |

200 |

|

TOTAL |

21.33 |

320 |

|

|

|

|

|

3. Final Dough |

|

|

|

Wheat Levain [from above] |

26.67 |

400 |

|

Rye Sourdough [from above] |

21.33 |

320 |

|

Strong White Flour |

75.33 |

1130 |

|

Salt |

1.8 |

27 |

|

Water |

43.34 |

650 |

|

TOTAL |

168.47 |

2527 |

|

Total Hydration |

66.67% |

- |

|

Total Pre-fermented Flour |

24.67% |

- |

Method:

- Build both the rye sour and wheat levain using 2 elaborations plus stock starters, over a 30 hour period for the Rye and a 15 hour period for the Wheat.

- For the final dough, first of all use autolyse, combining flour, water and rye sour. Leave for 40 minutes

- Combine autolyse with wheat levain and mix for 5 minutes. Add salt and mix a further 5-10 minutes.

- Ferment in bulk, covered, for 2 hours. Stretch and fold, and leave a further half hour.

- Scale at 1.5kg + 1kg piece. Mould round. And place upside down in prepared Bannetons.

- Proof in the fridge for 1 hour, then ambient for 2 hours prior to baking.

- Pre-heat oven to 250°C, hold for 10 minutes before setting the bread onto hot bricks.

- Fill a roasting pan with hot stones with boiling water for steam, and cut the top of the loaves before setting to bake. After 15 minutes drop the heat to 220°C. After another 30 minutes drop the temperature to 200°C and completely bake out each loaf.

- Cool on wires

-

Ok, so there is evidence that my hands are not so clean; please don't make comments about this oversight on my part; the photographs are posted to be instructive and helpful. Thanks for appreciating this!

-

The finished dough was strong, resulting in a lovely finished flavour in the bread. How I wish domestic ovens had sufficient power to do these large loaves full justice.

-

Best wishes

-

Andy

- ananda's Blog

- Log in or register to post comments

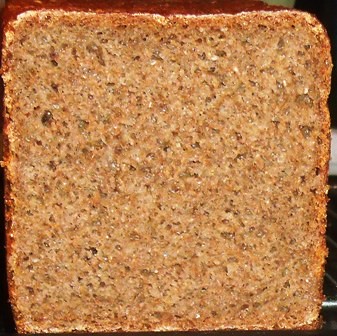

Andy, If my sight doesn't deceive me the crumb came out really translucent. Generally I prefer tighter crumbs, but I have to say that this bread is fascinating.

How much starter did you use in the preferments? The usual 4-5% respect to flour?

As for the rye one, what to say? I never used molasses so far, but it's my only bread and I know what a delight it is!

Hi Nico,

I'm just too busy to record full detail of elaboration these days. However, I generally carry between 50 and 100g of stock starter for both the wheat levain and rye sour. My best guess is that probably makes 80g worth of flour to start the whole thing off. That's 5.3% of the total flour in the formula. Of course, the key is to make sure the rye is soured over 18 hours, whereas the leaven is treated to a more gradual fermentation to give a different balance of wild yeasted leavening power to acid bacteria.

You would love the molasses, I'm sure. It has improving aspects in the dough, gives a bit of sweetness, and, colour, and just a tinge of bitterness to balance off all the complex flavours....yum!

Thanks for your comment, and best wishes

Andy

Both of your loaves are remarkable Andy, but I'm particularly taken with the 80% rye and its incredibly large crumb . I honestly can't say I've seen anything quite like it in a high ratio rye before. How much of a factor do you think the liquid levain was in what's obviously a very balanced and well controlled fermentation? The paste itself appears to be sitting well down in the pan, so quite a rise for a rye bread of this type in my experience. Talk about pushing the envelope!

Such a contrast in crumbs between the two. Naturally, I look at the photos first then read the text and formula, so I was quite surprised when I read your Pain au Levain had just a 66% overall hydration. The large, open, chewy looking crumb would suggest a much higher water content to me, but that's based on what I expect from a Canadian flour.

Not that I really expect to achieve the same results you have with these formulas, I certainly appreciate that you've made them available to all of us on this forum. You definitely know how to raise the bar for the rest of us wannabees. Brilliant baking Andy!

Very Best Wishes,

Franko

Hi Franko,

I really appreciate your generosity, thank you.

For the rye, yes, you are right that the volume in the finished loaf was extremely pleasing. This is especially the case, given the original formula from Hamelman does use baker's yeast, and I had no need for this step at all. I think I have to put this down to the long number of years I've been working with rye sourdough, and the eminent fermentability of the Bacheldre dark rye flour. This just means I've managed to create and maintain a really powerful starter.

Interesting concept: if you look at the excellent work of Mini, and read through Hamelman, you discover they both prefer a stiffer starter. So, why do I use the liquid starter? Firstly, because that is the way I learnt. Given that involved maintaining in excess of 600kg of rye sour in 12 giant plastic bins, you get the idea of how much rye bread we made on a daily basis. And the secret was always to ferment the culture right through for a full 18 hours. To me, a stiffer starter may well mean longer cycle.

For all that, I have used the Detmolder system from time to time, and really enjoyed the attention to detail, learning levels involved, and the taste of the finished bread. BUT, I use what I know to work; and, it does!

As for hydration in the Pain au Levain, I am not of the "wetter the better" school. I try to hydrate the dough correctly; I hope the photos above show that to be the case. Very wet dough is for ciabatta and foccaica. Pizzas are pretty soft too. Other than that, I make very few wheat doughs more than 70% hydration, unless we are talking the wondrous 100% wholewheat breads, or, breads with soakers, particularly gelatinised soakers. Do note, however, that my rye sourdough loaf is hydrated at 85%, whereas the original Hamelman formula is at 78%, and with a high gluten flour.

You could be right about Canadian flour, but I'm not sure. I use a beautiful all-Canadian flour in College. Hydration for standard loaves is around 63%. For hearth breads, etc, it's the same 66% upwards, with ciabatta at about 80%!

All good wishes

Andy

The rye and the 2-levain bread together make me wonder about making a rye with 2 rye sours - one firm, the other liquid. I'm wondering if one could shortcut the Detmolder 3-stage approach by fermenting 2 sours simultaneously then combining them in the final dough.

Have you every tried that?

My pullman pan is sitting on a pantry shelf complaining of neglect. It's pathetic.

David

Hi David,

thanks for your comments.

I think your idea may well have some mileage. So you refresh one culture to create good wild yeast activity. Then split that in two, and use one to create a stiff starter with a long and slightly cooler cycle, and the other to create a shorter cycle with a thinner paste and warmer conditions. Worth a try!

My only thought is whether Hamelman recommends the 3 stages as a means to produce a balance of acid and wild yeast within the mix as a whole. You know who I'd be talking to about this? Try Debra, I'll bet she has the answer!

Now, get that Pullman Pan prepared!

I'll post over on your miche thread about the questions you asked, as soon as I can. I would recommend, in the meantime to get a really good look at the photos of the dough above in its various stages. If you read Franko and Eric's comments, you'll get where I'm coming from. Dough quality is high, and hydration levels are not so high as many on here are used to. However, for the high extraction flour, I'd be up near 70%, if not slightly over!.

Very best wishes

Andy

Thank you for these interesting loaves, with much useful detail.

What is the ambient temperature for the fermentation time you give?

Hi Louie

Thank you for posting here.

I'd say the bulk fermentation temperature was in the mid 20s *C. So, too the final periods of fermentation

Best wishes

Andy

Remarkable looking loaves Andy! My Pullman is also complaining of neglect recently. Thank you for the inspiration.

I'm taken by the look of the dual levain SD dough. It looks so much like my 75% hydration doughs and yet it is only 66.67%. The crumb is evidence of a high level of activity. Well done Professor!

Eric

Hi Eric,

Remember the wonderful white? I'm really happy with the way my leavens are performing right now. I seem to have established a good feeding regime, and be baking regularly enough at home to maintain these cultures very effectively. A bit of extra attention in the elaboration seems to produce the best end results.

Hydration levels? I've said it all above, to Franko.

As with David; get that Pullman Pan out, you bake fantastic rye breads mainman!

Thank you so much for your encouraging and generous words

Best wishes

Andy

Your right 'not for changing'. I can taste it, the crumb speaks! This is a rye I could eat whole loaf myself and the SD too!

Sylvia

Hi Sylvia,

yes, the crumb speaks! I love rye bread more and more. Alison likes it the best of all the breads I make. And, this particular loaf turned out better than ever.

No reason to change, as you say; thank you for your post

Best wishes

Andy

You really manage to get a nice crumb from a very wet rye dough! And I suspect the blackstrap molasses emboldens the already bold rye flavor.

I love Hamelman's mixed starter pain au levain - and the crumb on your loaves is one of the reasons, along with the nice subtle mix of flavors. So I have a question: why do you leave out the wheat levain until after the autolyse in your final mix? I know there must be something behind the decision, so I'm most curious.

Good baking, and why change when you can produce loaves such as those!

Larry

Hi Larry,

It's really good to hear from you!

I'm used to rye breads being pretty wet. To me, this paste was spot-on. That also takes into account Shiao-Ping's very useful comment last year about the empirical affect of using molasses. Although here, it was only at 5%.

Daisy_A will no doubt attest to this: our Bacheldre Rye flour lurves water too. Honestly, 85% hydration is a constant target and expectation I have with these rye breads. You just have to take that into account when baking off a lump of paste weighing the best part of 2kg, of which almost 900g is water! But "rye needs a lot of water" is a good baseline

As for the 2 leavens; it is my formula, although you know how much I follow the work of Hamelman and what I learn from it. Jeffrey Hamelman himself recommends this procedure for autolyse, if I'm not mistaken? This is what he has to say on page 9.

He goes on to write:

My guess is that your curiosity is answered

All good wishes

Andy

I'm familiar with Hamelman's exception to include liquid perferments/levains during autolyse because of the necessity of the extra water to adequately mix with the flour. But there seems so little difference in the hydration of your rye sour versus wheat levain (50g) that it didn't occur to me to include the one and not the other. On the other hand, it now occurs to me that doing so does allow you to withhold some levain (along with the salt) and thus contributes to the effectiveness of the autolyse.

In all events, the bread is testament to your approach!

Larry

Hi Larry,

I start from the base of not including leaveners or salt in any autolyse.

Then I apply 2 exceptions. First is any liquid starters. Second is dried yeast. However, since I use dried yeast only once in a blue moon in any combination, I can't think of a time it's come anywhere near a dough I was preparing using autolyse!

So, I automatically go with your second idea, and don't really relate to the first one.

Here's a thought: salt is left out. The hydration in the autolyse is 68%. So that makes a lot more water available in this first stage to induce enzymatic reactions by hydrating starch and protein. If I added the wheat levain, that would reduce the water availability. And the flour in the leaven is pre-fermented, so it has no use for autolyse.

I've never really questioned Hamelman's recommendations for autolyse. I stick to them because I believe them to be completely correct.

Many thanks, as always, for your kind words

All good wishes

Andy

Hi Peter,

I see you are from the UK and have only just joined TFL. In which case a very warm welcome to you!

I have some good news, and, maybe, not such good news for you.

Let's start with the obstacles and go from there. If you are to build up a viable colony of wild yeast and bacteria and thus create a strong starter, then yes, you really will be making life so much easier for them if you can create a temperature they like. The key is to build your starter very strong in the first place, through correct feeding and use of temperature. You could try a heat jacket, or a plant propogator. Some people on here use their oven with just the oven light switched on. What about a large plastic box with a good lid, and a decent light bulb inside? There must be some means you can come up with: you need a temperature range say 28 - 35*C to get the thing moving.

Now the better news. Once you have a good starter, it will be less temperature dependent for success. This is especially the case if you use Dark Rye, or Whole Rye flour, as this is so eminently fermentable. I am not saying you will get the same level of performance as if you had a warm environment, as you will not. But, once your culture is well-established, it will become viable, and multiply, even at cooler temperatures.

There are debates about age of sourdough cultures. Some bakers like to use their starters only for short periods, then discard and start afresh. Others, me included, like to keep the same culture going and build its strength through feeding and frequent use. Again, especially rye. Much will come down to experience, Peter, and to gain that you will just have to experiment. Don't give up, please, as you will get there. I do advise finding someway to warm up your leavens and doughs, however. It will make a lot of difference I promise.

Many thanks for commenting here, and for your kind words. If you need further specific advice, you just have to ask.

Best wishes

Andy

Meanwhile over here...

Let's start with the ever difficult topic of flour, and how it differs both sides of the pond.

Yes, I did specify a strong white flour. I used Allinson Strong White Bread Flour. Granted it is an "industrial" flour, but I was quite impressed with its performance. It specifically references use for bread and pizza, which I thought was quite interesting given the need [sorry] for plenty of extensibility in pizza dough.

The protein read is 12.1g per 100g of flour. I do insist, as ever, that the headline figure can only ever be a guide. The quality of the glutenin and gliadin fractions is what really counts. And, these 2 fractions do not account for the total protein content, as other proteins such as albumens and globulins are also found in the wheatberry. Anyway, it's a pretty good flour, but not one of those superstrong varieties.

So, what of the much-respected King Arthur All-Purpose flour? A scout on KA website can take you here: http://www.kingarthurflour.com/professional/specifications-conventional-bakery-flour.html The flour listed as Sir Galahad is the same as the grade sold as All-Purpose at the retail end of things, according to Larry. I consider him an extremely reliable source on matters King Arthur.

A protein read of 11.7% is scarcely any different to the 12.1% I used really. Added to which, the ash content in the flour is less than 0.5%, so equivalent to calling it a Type 48 French flour [yes, I know it is usually sold at Type 45 and 50] Granted, the Allinson does not quote ash content, but I'd lay money on it being higher than 0.48% Higher ash content means greater mineral content derived from the outer parts of the grain. By extension, I take that to mean there will be more protein from the outer part of the grain; protein which does not contribute to gluten content.

My other point would be that, having watched the video of Hamelman mixing the baguette dough, I really do ask for serious consideration of dough development from what really is a high quality flour...and I mean for bread! For the most part [there are a few exceptions, apparently], if anyone made bread with plain flour from the UK, it would not turn out well. We do not have "All Purpose" as a regular High Street grade. Believe me, I do understand the counsel not to rely on the really high gluten flours for anything except certain specialist products [bagels come to mind, Lindy your beautiful examples in particular!]...I agree with that. But North American AP, especially this King Arthur brand, is clearly a high quality flour, on a par with the flour type I used in the formula above. So, I don't believe it is to do with choice of wheat flour; but I do think it could well be to do with the rye sour performance.

One little aside, as I know Louie made a point of trying to follow all the procedures above very carefully. The final proof only had a period of refrigeration to allow for successful oven production schedule. At the point when I shaped the dough for final proof, I was about to load the rye sourdough tinned loaf into my oven. That loaf was 2kg in weight, plus the metal of the Pullman Pan, necessitating a long slow bake. So, the period in the chiller was only necessary to retard final proof to accommodate other breads in production.

On to levels of development, and why I moved the discussion back here. You can clearly see that I mixed the dough to achieve window pane. I received able assistance from my wife, Alison, to capture this photo. So, have you all watched the Hamelman video and listened to his comments on not over-mixing? At this point we need to consider what levels constitute over-mixing. You see, I would argue that the dough coming off Jeffrey's lovely spiral mixer was pretty well developed, especially compared to the standards realistically achievable in a home environment. Hamelman's worked all over the world, and he's been around a long time. He will, like me, be quite used to bakers throwing seemingly endless amounts of energy into a dough. He specifically references caratenoid pigments in the video, and he gives mixing time, and information on number of revolutions of the bowl. I have quite a bit of experience of working with plant bakers in the UK, who use high speed mixers, under vacuum to turn out dough for their beloved Chorleywood Bread Process. This is what I imagine Jeffrey Hamelman to be counseling against. I don't believe he is saying "you should under mix the dough"; instead, like me, it is a case of mixing to achieve good development without subjecting the dough to the stresses of high energy. Please bear in mind that Hamelman's book was primarily written for professional bakers. The section on mixing is testament to this, in its discussion of spiral mixers, revolutions, etc.

So, my text above does advocate dough development. For all that, I do work my dough up by hand. It is quite possible to overmix dough in a machine on a domestic scale. However, one look at the crumb of the loaf produced by louie quickly dispels any notion that the dough was over-mixed.

The photos speak for themselves in respect of dough quality. The hydration proved entirely correct throughout. Combining salt, autolyse and wheat levain produced a fairly soft and sticky mass to start with. But, look how it came together smooth, silky, and it window paned. From there, note the picture of the relaxed dough, then the effect of S&F. Not quite as good as seeing Jeffrey Hamelman patting his dough affectionately during the S&F phase, but I'm still really pleased with this.

Then there is shaping. Lindy makes this point, and it is so true how important it is to use a strong hand, but need for real care and sensitivity in the moulding. I know my hand is dirty [SORRY!], but I think these pictures are representative. Firstly to achieve a nice shape to the dough piece, then mould it up tightly, but without tearing the dough.

I had an interesting discussion develop with David Snyder, here: http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/21644/miche-hit#comment-152745

I so wish I could have baked these loaves in my deck oven in College. The core of the big loaf had a tighter crumb than the extremities. Whatever tricks we home bakers use in the oven, it is not possible to match up exactly the benefits of the extra power of the commercial beast...except with the wood-fired oven of course!!!

So, if a more open crumb is your one big aim, then you'll be best off going down Khalid's recommended route, and produced a wetter dough for spring in the oven. My purpose is to demonstrate the same can be achieved used a dough which is hydrated at a slightly lower level, and is mixed to a good degree of development. For the big miche, good bottom heat, plus steam injection really helps to complete the result throughout the whole loaf. But that is the case for any loaf of this type.

A little thought to end: Hydration. Sir Galahad is listed at 61% in the reference I list above. I look to achieve 63% in a standard white panned bread, which I take as a standard test, and expect the figure quoted by KAF to be for a similar type dough. I use an All Canadian flour for this in College, and the manufacturers rightly describe it as "world class flour" [protein content is again, just over 12%]Yet, I increased hydration to nearly 67% here. My point is that, actually, this is a high hydration dough!! It just is not "the wetter the better" on this particular blog poster's page. The right water for the dough you are trying to make, and correct hydration levels to satisfy the starches, proteins and fibre in the flour of choice.

All good wishes

Andy

One clarification: the gluten measurement system used in the US (probably all of North America, but I'm not certain:-) is subtly different from the one used in Europe (apparently uncluding the UK). The American measurement system is based on a supposed moisture content of 14%, while the European measurement system is based on a supposed moisture content of 0%.

The formula for converting seems to be: AmericanPercentage x (86/100) = EuropeanPercentage (or the other direction AmericanPercentage = (100/86) x EuropeanPercentage)

So that 12.1% in the UK would be rated 14% in the US.

Hi Chuck,

Thanks for posting. Yes, European flour testing is done assuming nil moisture, this is true.

However, I have not given figures from test results, I have used the nutritional information on the side of the bag. This would take account of the moisture in the flour.

So the protein read is as I stated: 12.1g per 100g. Using the American classification that remains 12.1%, not that ambitious 14% you suggest. That would be classed as Superstrong, or High Gluten flour over here; I did not use very strong flour, as explained.

Best wishes

Andy

Hi DaisyA,

Thanks for this. The Allinson is a good flour, but there will be a lot more British wheat in the grist. However, the specifications will be pretty similar, I reckon!

Best wishes

Andy