I am far from a sourdough expert. I’ve only been baking sourdough since February, and I still have a lot to learn about shaping, scoring and proofing to perfection.

However, there is one thing I have learned well: how to squeeze more flavor out of my naturally sweet starter. Here's the basic tips.

1) Keep the starter stiff

2) Spike your white starter with whole rye

3) Use starter that is well-fed

4) Keep the dough cool

5) Extend the rise by degassing

6) Proof the shaped loaves overnight in the fridge

Photos and elaboration follow.

It’s a common lament that I see on bread baking forums – Why isn’t my sourdough sour?

Personally, I blame Watertown. My evidence? I gave some of my starter to a friend who lives six miles away in Lexington. Within 6 weeks, she was making sour tasting sourdough. Her local yeastie beasties are clearly more sour than mine.

I don’t know what it is about the microflora that live in the little hollow between the hills that I occupy in Watertown, Mass., but treated traditionally, my white starter and my whole wheat starter pack as much sour taste as a loaf of Wonder Bread. That’s not to say that the loaves don’t taste nice. They do. They’re wheaty with a touch of a buttery aftertaste.

But they don’t taste sour, which is how I think sourdough ought to taste.

Anyway, I’ve finally figured out how to get the tangy loaves I love. If you’re facing the same sweet trouble as me, perhaps some (or all) of these tips will help.

1) Keep your starter stiff:

Traditionally, sourdough starter is kept as a batter. The most common consistency is to have equal weights of water and flour, also known as 100% hydration because the water weight is equal to 100% of the flour weight. That’s roughly 1 scant cup of flour to about ½ cup of water. Jeffrey Hammelman keeps his at 125%, and quite a few folks keep theirs at 200% (1 cup water to 1 cup flour).

I keep my sourdough starter at 50% hydration, meaning that for every 2 units of flour weight, I add 1 unit of water.

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white.

There are two basic types of bacteria that flourish in a sourdough starter. One produces lactic acid, which gives the bread a smooth taste, sort of like yogurt. It does best in wet, warm environment. The other makes acetic acid, the acid that gives bread its sharp tang. These bacteria prefer a drier, cooler environment.

(Or so I've read, anyway. I ain't no biochemist; I just know what they print in them books.)

A hydration of 50% is pretty stiff, especially for a whole-wheat starter. You really have to knead strongly to convince the starter to incorporate all the flour.

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white.

There are two basic types of bacteria that flourish in a sourdough starter. One produces lactic acid, which gives the bread a smooth taste, sort of like yogurt. It does best in wet, warm environment. The other makes acetic acid, the acid that gives bread its sharp tang. These bacteria prefer a drier, cooler environment.

(Or so I've read, anyway. I ain't no biochemist; I just know what they print in them books.)

A hydration of 50% is pretty stiff, especially for a whole-wheat starter. You really have to knead strongly to convince the starter to incorporate all the flour.

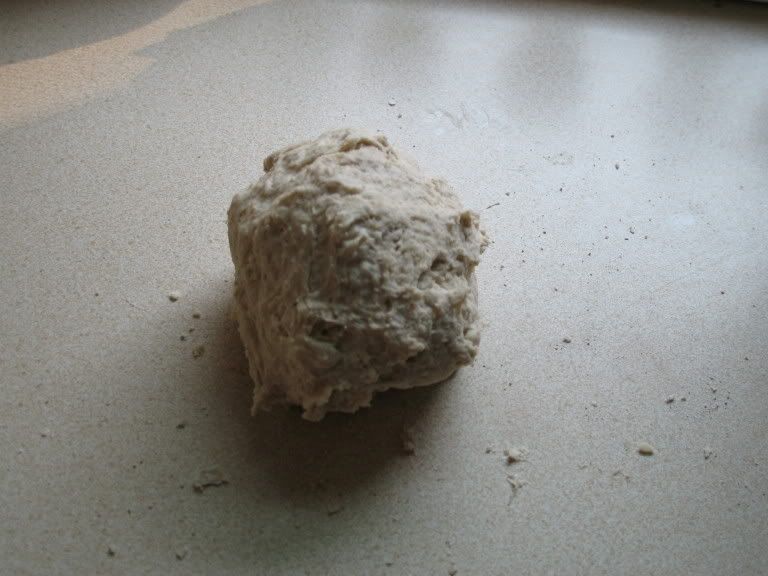

For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit.

For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit.

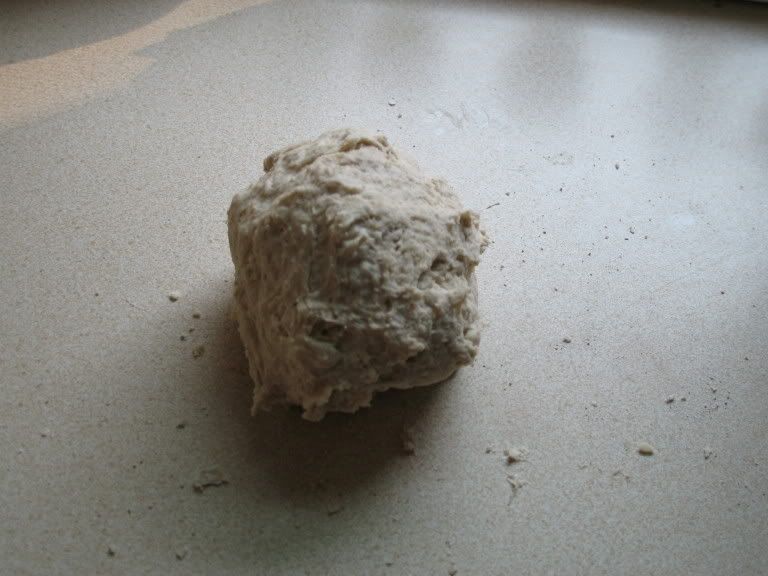

Here's what it looks like after kneading.

Here's what it looks like after kneading.

And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

Conversion from 100% to 50% isn't hard to do if you've got a kitchen scale.

Take 2 ounces of your 100% starter. Then add 5 ounces of flour and 2 ounces of water. This should give you 9 ounces of starter. Leave it overnight, and it should be ripened in the morning.

From there on out when you feed it, add 1 unit of water for every 2 units of flour. I'd recommend feeding it 2 or 3 more times before using it, though, so that the yeast and bacteria can acclimate to the new environment.

There are additional advantages to a stiff starter beyond producing a more sour bread.

First, a stiff starter is easier to transport. Just throw a hunk into a bag, and you’re done.

Supposedly, the stiff stuff keeps longer than the batters. You can leave stiff starter in the fridge for months, or so I hear, and it can still be revived. Never tried it myself, though, so don't take my word for it.

Finally, the math for feeding is easy at 50% hydration, much easier than 60% or 65%. Just feed your starter in multiples of threes. For exmaple, if I’ve got 3 ounces of starter and I need to feed it, I'll probably triple it in size. To get six additional ounces for food, I just add 4 ounces flour and 2 ounces water. Piece of cake.

Converting recipes isn’t hard either. First, figure out the total water weight and total flour weight in the original recipe, including what's in the starter. If the recipe calls for a 100% hydration starter, then half of the starter is flour and the other half is water. Divide it accordingly to get the total flour and total water weights in the final dough.

Now, add the total water and total flour together. Take that figure and multiply by 0.30. This will tell you how much stiff starter you’ll need.

Last, subtract the amount of water in the stiff starter from the total water in the final dough, and the amount of flour in the stiff starter from the total flour in the final dough. The results tell you how much flour and water to add to the starter to get the final dough. Everything else remains the same.

2) Spike your white starter with whole rye flour:

It doesn’t take much. Currently, my white starter is about 10-15% whole rye. Basically, for every 3 ounces of white flour that I feed the starter, I replace ½ ounce with whole rye. That small portion of rye makes a big difference in flavor. Rye is to sourdough microflora as spinach is to Popeye. It’s super-food that’s easily digestible and nutrient rich. That’s why so many recipes for getting a starter going from scratch suggest you start with whole rye.

And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

Conversion from 100% to 50% isn't hard to do if you've got a kitchen scale.

Take 2 ounces of your 100% starter. Then add 5 ounces of flour and 2 ounces of water. This should give you 9 ounces of starter. Leave it overnight, and it should be ripened in the morning.

From there on out when you feed it, add 1 unit of water for every 2 units of flour. I'd recommend feeding it 2 or 3 more times before using it, though, so that the yeast and bacteria can acclimate to the new environment.

There are additional advantages to a stiff starter beyond producing a more sour bread.

First, a stiff starter is easier to transport. Just throw a hunk into a bag, and you’re done.

Supposedly, the stiff stuff keeps longer than the batters. You can leave stiff starter in the fridge for months, or so I hear, and it can still be revived. Never tried it myself, though, so don't take my word for it.

Finally, the math for feeding is easy at 50% hydration, much easier than 60% or 65%. Just feed your starter in multiples of threes. For exmaple, if I’ve got 3 ounces of starter and I need to feed it, I'll probably triple it in size. To get six additional ounces for food, I just add 4 ounces flour and 2 ounces water. Piece of cake.

Converting recipes isn’t hard either. First, figure out the total water weight and total flour weight in the original recipe, including what's in the starter. If the recipe calls for a 100% hydration starter, then half of the starter is flour and the other half is water. Divide it accordingly to get the total flour and total water weights in the final dough.

Now, add the total water and total flour together. Take that figure and multiply by 0.30. This will tell you how much stiff starter you’ll need.

Last, subtract the amount of water in the stiff starter from the total water in the final dough, and the amount of flour in the stiff starter from the total flour in the final dough. The results tell you how much flour and water to add to the starter to get the final dough. Everything else remains the same.

2) Spike your white starter with whole rye flour:

It doesn’t take much. Currently, my white starter is about 10-15% whole rye. Basically, for every 3 ounces of white flour that I feed the starter, I replace ½ ounce with whole rye. That small portion of rye makes a big difference in flavor. Rye is to sourdough microflora as spinach is to Popeye. It’s super-food that’s easily digestible and nutrient rich. That’s why so many recipes for getting a starter going from scratch suggest you start with whole rye.

Here I am, about to add rye to "Barney Barm," my white starter. I haven’t added rye to my whole-wheat starter, though. It hasn’t needed it – there’s more than enough nutrients in the whole wheat to keep the starter party going strong.

3) Use starter that is well fed: Early in my search to sour my sourdough, I’d read that, if you leave a starter unfed and on the counter for a few days before baking, it will make your bread more sour.

I’ve found that’s not the case. The starter gets more sour, but the bread doesn’t taste very sour at all.

The better course is to take your starter out of the fridge at least a couple of days before you use it, and then feed it two or three times before you make the final dough. Healthy microflora make a more flavorful bread.

4) Keep the dough cool:

When I first started out, I was following recipes that called for the dough to be at 79 degrees, and I’d often put it in a fairly warm place to rise. Warmth kills sour taste. Nowadays, I add water that’s room temperature, not warmed, and aim for a much cooler rise, no higher than 75 degrees and often as low as 64.

Here I am, about to add rye to "Barney Barm," my white starter. I haven’t added rye to my whole-wheat starter, though. It hasn’t needed it – there’s more than enough nutrients in the whole wheat to keep the starter party going strong.

3) Use starter that is well fed: Early in my search to sour my sourdough, I’d read that, if you leave a starter unfed and on the counter for a few days before baking, it will make your bread more sour.

I’ve found that’s not the case. The starter gets more sour, but the bread doesn’t taste very sour at all.

The better course is to take your starter out of the fridge at least a couple of days before you use it, and then feed it two or three times before you make the final dough. Healthy microflora make a more flavorful bread.

4) Keep the dough cool:

When I first started out, I was following recipes that called for the dough to be at 79 degrees, and I’d often put it in a fairly warm place to rise. Warmth kills sour taste. Nowadays, I add water that’s room temperature, not warmed, and aim for a much cooler rise, no higher than 75 degrees and often as low as 64.

The cellar is your friend.

5) Extend the rise by degassing:

When I make whole wheat sourdough, I usually let the dough rise until it has doubled and then degass it by folding until it rises a second time. Along with cool dough, this means the bulk fermentation usually lasts 5-6 hours.

When I’m making pain au levain or some other white flour sourdough, I usually have the dough very wet, so it needs more than one fold to give it the strength it needs. In this case, I fold once at 90 minutes and then again after another 90 minutes. Usually, the full bulk rise lasts about 5 hours.

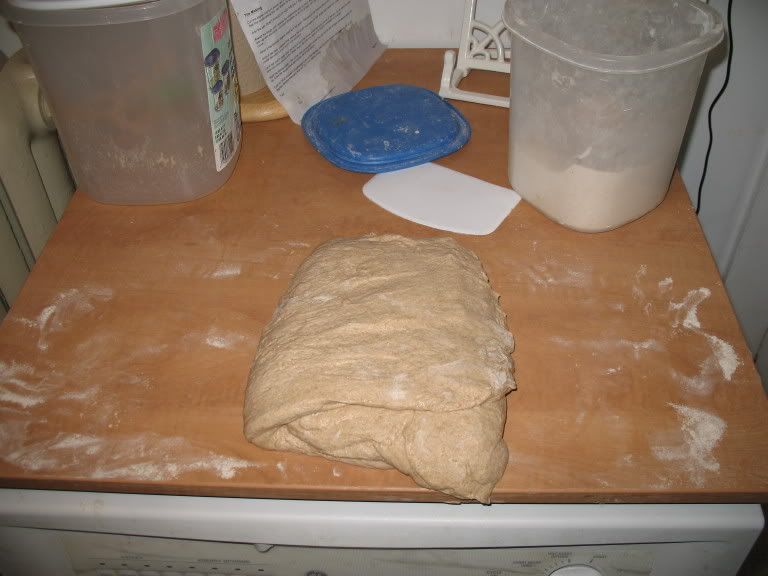

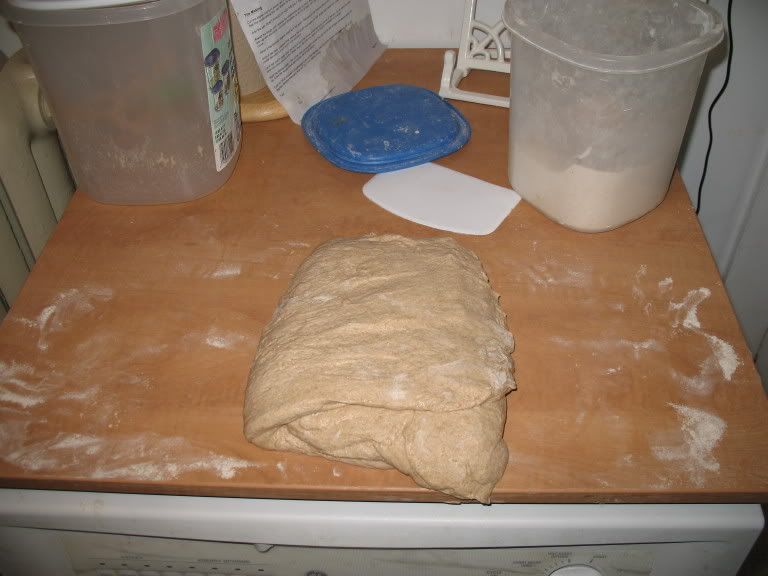

Here's a sequence showing how I fold my whole-wheat sourdough.

The cellar is your friend.

5) Extend the rise by degassing:

When I make whole wheat sourdough, I usually let the dough rise until it has doubled and then degass it by folding until it rises a second time. Along with cool dough, this means the bulk fermentation usually lasts 5-6 hours.

When I’m making pain au levain or some other white flour sourdough, I usually have the dough very wet, so it needs more than one fold to give it the strength it needs. In this case, I fold once at 90 minutes and then again after another 90 minutes. Usually, the full bulk rise lasts about 5 hours.

Here's a sequence showing how I fold my whole-wheat sourdough.

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet).

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet).

Stretch it to about twice its length.

Stretch it to about twice its length.

Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal.

Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal.

Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.

6) Proof the shaped loaves overnight in the fridge:

This final touch really brings out the flavor. So much so that, if you’ve incorporated all the other suggestions, proofing overnight might make your bread a bit too sour for your taste. My wife and I like it assertively sour, however, so this step is a must.

Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.

6) Proof the shaped loaves overnight in the fridge:

This final touch really brings out the flavor. So much so that, if you’ve incorporated all the other suggestions, proofing overnight might make your bread a bit too sour for your taste. My wife and I like it assertively sour, however, so this step is a must.

Normally, I’d suggest proofing your loaves on the top shelf where it’s warmest, so as not to kill off any yeast, but I find that if I put my loaves in the top, they’re ready in about 4-6 hours, at which time I’m usually sound asleep. So I started putting them in the bottom, and had better luck.

I hope this helps those of you who dread pulling another beautiful loaf from the oven, only to find it looks better than it tastes. Best of luck!

Normally, I’d suggest proofing your loaves on the top shelf where it’s warmest, so as not to kill off any yeast, but I find that if I put my loaves in the top, they’re ready in about 4-6 hours, at which time I’m usually sound asleep. So I started putting them in the bottom, and had better luck.

I hope this helps those of you who dread pulling another beautiful loaf from the oven, only to find it looks better than it tastes. Best of luck!

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white.

There are two basic types of bacteria that flourish in a sourdough starter. One produces lactic acid, which gives the bread a smooth taste, sort of like yogurt. It does best in wet, warm environment. The other makes acetic acid, the acid that gives bread its sharp tang. These bacteria prefer a drier, cooler environment.

(Or so I've read, anyway. I ain't no biochemist; I just know what they print in them books.)

A hydration of 50% is pretty stiff, especially for a whole-wheat starter. You really have to knead strongly to convince the starter to incorporate all the flour.

Barney Barm, my white starter is on the left; Arthur the whole wheat starter on the right. The bran and germ in whole wheat absorb a lot of water, so that starter is even stiffer than the white.

There are two basic types of bacteria that flourish in a sourdough starter. One produces lactic acid, which gives the bread a smooth taste, sort of like yogurt. It does best in wet, warm environment. The other makes acetic acid, the acid that gives bread its sharp tang. These bacteria prefer a drier, cooler environment.

(Or so I've read, anyway. I ain't no biochemist; I just know what they print in them books.)

A hydration of 50% is pretty stiff, especially for a whole-wheat starter. You really have to knead strongly to convince the starter to incorporate all the flour.

For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit.

For example, here's my white starter after I've done my best to mix it up in the bucket. Time to knead a bit.

Here's what it looks like after kneading.

Here's what it looks like after kneading.

And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

Conversion from 100% to 50% isn't hard to do if you've got a kitchen scale.

Take 2 ounces of your 100% starter. Then add 5 ounces of flour and 2 ounces of water. This should give you 9 ounces of starter. Leave it overnight, and it should be ripened in the morning.

From there on out when you feed it, add 1 unit of water for every 2 units of flour. I'd recommend feeding it 2 or 3 more times before using it, though, so that the yeast and bacteria can acclimate to the new environment.

There are additional advantages to a stiff starter beyond producing a more sour bread.

First, a stiff starter is easier to transport. Just throw a hunk into a bag, and you’re done.

Supposedly, the stiff stuff keeps longer than the batters. You can leave stiff starter in the fridge for months, or so I hear, and it can still be revived. Never tried it myself, though, so don't take my word for it.

Finally, the math for feeding is easy at 50% hydration, much easier than 60% or 65%. Just feed your starter in multiples of threes. For exmaple, if I’ve got 3 ounces of starter and I need to feed it, I'll probably triple it in size. To get six additional ounces for food, I just add 4 ounces flour and 2 ounces water. Piece of cake.

Converting recipes isn’t hard either. First, figure out the total water weight and total flour weight in the original recipe, including what's in the starter. If the recipe calls for a 100% hydration starter, then half of the starter is flour and the other half is water. Divide it accordingly to get the total flour and total water weights in the final dough.

Now, add the total water and total flour together. Take that figure and multiply by 0.30. This will tell you how much stiff starter you’ll need.

Last, subtract the amount of water in the stiff starter from the total water in the final dough, and the amount of flour in the stiff starter from the total flour in the final dough. The results tell you how much flour and water to add to the starter to get the final dough. Everything else remains the same.

2) Spike your white starter with whole rye flour:

It doesn’t take much. Currently, my white starter is about 10-15% whole rye. Basically, for every 3 ounces of white flour that I feed the starter, I replace ½ ounce with whole rye. That small portion of rye makes a big difference in flavor. Rye is to sourdough microflora as spinach is to Popeye. It’s super-food that’s easily digestible and nutrient rich. That’s why so many recipes for getting a starter going from scratch suggest you start with whole rye.

And here's what it looks like 5 hours later once it's ripe.

Conversion from 100% to 50% isn't hard to do if you've got a kitchen scale.

Take 2 ounces of your 100% starter. Then add 5 ounces of flour and 2 ounces of water. This should give you 9 ounces of starter. Leave it overnight, and it should be ripened in the morning.

From there on out when you feed it, add 1 unit of water for every 2 units of flour. I'd recommend feeding it 2 or 3 more times before using it, though, so that the yeast and bacteria can acclimate to the new environment.

There are additional advantages to a stiff starter beyond producing a more sour bread.

First, a stiff starter is easier to transport. Just throw a hunk into a bag, and you’re done.

Supposedly, the stiff stuff keeps longer than the batters. You can leave stiff starter in the fridge for months, or so I hear, and it can still be revived. Never tried it myself, though, so don't take my word for it.

Finally, the math for feeding is easy at 50% hydration, much easier than 60% or 65%. Just feed your starter in multiples of threes. For exmaple, if I’ve got 3 ounces of starter and I need to feed it, I'll probably triple it in size. To get six additional ounces for food, I just add 4 ounces flour and 2 ounces water. Piece of cake.

Converting recipes isn’t hard either. First, figure out the total water weight and total flour weight in the original recipe, including what's in the starter. If the recipe calls for a 100% hydration starter, then half of the starter is flour and the other half is water. Divide it accordingly to get the total flour and total water weights in the final dough.

Now, add the total water and total flour together. Take that figure and multiply by 0.30. This will tell you how much stiff starter you’ll need.

Last, subtract the amount of water in the stiff starter from the total water in the final dough, and the amount of flour in the stiff starter from the total flour in the final dough. The results tell you how much flour and water to add to the starter to get the final dough. Everything else remains the same.

2) Spike your white starter with whole rye flour:

It doesn’t take much. Currently, my white starter is about 10-15% whole rye. Basically, for every 3 ounces of white flour that I feed the starter, I replace ½ ounce with whole rye. That small portion of rye makes a big difference in flavor. Rye is to sourdough microflora as spinach is to Popeye. It’s super-food that’s easily digestible and nutrient rich. That’s why so many recipes for getting a starter going from scratch suggest you start with whole rye.

Here I am, about to add rye to "Barney Barm," my white starter. I haven’t added rye to my whole-wheat starter, though. It hasn’t needed it – there’s more than enough nutrients in the whole wheat to keep the starter party going strong.

3) Use starter that is well fed: Early in my search to sour my sourdough, I’d read that, if you leave a starter unfed and on the counter for a few days before baking, it will make your bread more sour.

I’ve found that’s not the case. The starter gets more sour, but the bread doesn’t taste very sour at all.

The better course is to take your starter out of the fridge at least a couple of days before you use it, and then feed it two or three times before you make the final dough. Healthy microflora make a more flavorful bread.

4) Keep the dough cool:

When I first started out, I was following recipes that called for the dough to be at 79 degrees, and I’d often put it in a fairly warm place to rise. Warmth kills sour taste. Nowadays, I add water that’s room temperature, not warmed, and aim for a much cooler rise, no higher than 75 degrees and often as low as 64.

Here I am, about to add rye to "Barney Barm," my white starter. I haven’t added rye to my whole-wheat starter, though. It hasn’t needed it – there’s more than enough nutrients in the whole wheat to keep the starter party going strong.

3) Use starter that is well fed: Early in my search to sour my sourdough, I’d read that, if you leave a starter unfed and on the counter for a few days before baking, it will make your bread more sour.

I’ve found that’s not the case. The starter gets more sour, but the bread doesn’t taste very sour at all.

The better course is to take your starter out of the fridge at least a couple of days before you use it, and then feed it two or three times before you make the final dough. Healthy microflora make a more flavorful bread.

4) Keep the dough cool:

When I first started out, I was following recipes that called for the dough to be at 79 degrees, and I’d often put it in a fairly warm place to rise. Warmth kills sour taste. Nowadays, I add water that’s room temperature, not warmed, and aim for a much cooler rise, no higher than 75 degrees and often as low as 64.

The cellar is your friend.

5) Extend the rise by degassing:

When I make whole wheat sourdough, I usually let the dough rise until it has doubled and then degass it by folding until it rises a second time. Along with cool dough, this means the bulk fermentation usually lasts 5-6 hours.

When I’m making pain au levain or some other white flour sourdough, I usually have the dough very wet, so it needs more than one fold to give it the strength it needs. In this case, I fold once at 90 minutes and then again after another 90 minutes. Usually, the full bulk rise lasts about 5 hours.

Here's a sequence showing how I fold my whole-wheat sourdough.

The cellar is your friend.

5) Extend the rise by degassing:

When I make whole wheat sourdough, I usually let the dough rise until it has doubled and then degass it by folding until it rises a second time. Along with cool dough, this means the bulk fermentation usually lasts 5-6 hours.

When I’m making pain au levain or some other white flour sourdough, I usually have the dough very wet, so it needs more than one fold to give it the strength it needs. In this case, I fold once at 90 minutes and then again after another 90 minutes. Usually, the full bulk rise lasts about 5 hours.

Here's a sequence showing how I fold my whole-wheat sourdough.

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet).

First, turn the risen dough out on a lightly floured surface (heavily floured if your dough is very wet).

Stretch it to about twice its length.

Stretch it to about twice its length.

Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal.

Gently degass one-third of the dough, fold it over the middle, and degass the middle section to seal.

Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.

6) Proof the shaped loaves overnight in the fridge:

This final touch really brings out the flavor. So much so that, if you’ve incorporated all the other suggestions, proofing overnight might make your bread a bit too sour for your taste. My wife and I like it assertively sour, however, so this step is a must.

Do the same for the remaining side. Take the folded dough, turn it one-quarter, and fold once more before returning to the bowl or bucket to rise again.

6) Proof the shaped loaves overnight in the fridge:

This final touch really brings out the flavor. So much so that, if you’ve incorporated all the other suggestions, proofing overnight might make your bread a bit too sour for your taste. My wife and I like it assertively sour, however, so this step is a must.

Normally, I’d suggest proofing your loaves on the top shelf where it’s warmest, so as not to kill off any yeast, but I find that if I put my loaves in the top, they’re ready in about 4-6 hours, at which time I’m usually sound asleep. So I started putting them in the bottom, and had better luck.

I hope this helps those of you who dread pulling another beautiful loaf from the oven, only to find it looks better than it tastes. Best of luck!

Normally, I’d suggest proofing your loaves on the top shelf where it’s warmest, so as not to kill off any yeast, but I find that if I put my loaves in the top, they’re ready in about 4-6 hours, at which time I’m usually sound asleep. So I started putting them in the bottom, and had better luck.

I hope this helps those of you who dread pulling another beautiful loaf from the oven, only to find it looks better than it tastes. Best of luck!

I think I under stand how the math works but how do you come up with 30% of total weight for the firm starter why that number.

This is an interesting discussion of ways to maintain a sourdough culture. I tried several methods when I began making sourdough bread. Different books make quite different recommendations -- and different preferments for different specific beads within the same book. All very puzzling to a beginner. So one day I asked the baker whose work I have been observing.

His reply was, "I'm not a good person to ask. I do everything the same way." He maintains his culture at 125% hydration, feeds it twice a day with half wheat and half rye flour, and uses a factor of eight. Sourdough culture is one eighth of the flour in a batch of bread, something like that. His culture is very lively with all that feeding and the warmth of the huge wood-fired oven in the bakery.

Whatever he said, I have had success with all kinds of wholegrain and white bread, including 100% whole rye bread, doing this:

To summarize, I have one kind of sourdough culture and then make a preferment for each bread using the flour for that particular recipe.

In my (very limited) experience with sour dough, every thing I have read indicates that the bacteria (candida milleri, saccharomyces exiguus and lactobacillus sanfranciscensis) are the same, regardless of the flour used.

As for the the fluid on top, I also poured it off once and did not like the results. I stir it back in and use it.

Thought I'd just mention that since this thread popped up. My starters don't have hooch anymore. I haven't seen hooch on my sourdough in years! Keep it fed and it will feed you!

This is the Topic that got me on to firmer starters and am I glad! Thank you again JMonkey!

Consider yourself bear hugged! :)

To add a generalization:

Although we tend to think of making and baking bread as building and creating something "magic," it is sometimes helpful to think of making dough as a degenerative process.

Once water is added to flour, the flour starts to autolyse and decompose, we add ingedients, change temperatures, speed up decomposition by adding more yeast and sourdough and then slow it down trying to bake the dough when the flavor is to our liking but hasn't lost all of its ability to still stretch and rise to bake into the foodstuff we call "Bread."

Flour starts out very alkaline and slides thru the pH scale until it is very acid. The closer we get to acid end of the scale the trickier it gets to control and still manage a decent loaf before its stucture breaks down too much. Fresh flour and water at one end of the scale, used up exhausted dough at the other end. Even then, we can use this broken down dough to further or speed up the fermenting (decaying) process in another batch of dough going up and down the scale until we're satisfied enough to shape and bake it.

Mini

With your encouragement I divided my Carl Griffin's starter and made part of it very much stiffer than usual. I then used that starter to bake a wholegrain loaf this weekend. It turned out great! I couldn't believe that I was raising bread dough with 10 grain cereal, flax seed, and mostly whole wheat flour as light as it rose in both the bowl and the loaf pan - and absolutely no commercial yeast!

I'd like to post a picture, but the little green tree is not cooperating - or it could be me. If you reply here, please tell me how to post a pic.

Thanks for your expertise and helping all of us along on our sourdough adventures.

Teresa

- Make sure that at least the final rise at about 85 degrees F: It really does make a huge difference in flavor and rise. The loaf I made today was just bursting out of the pan after only 2 hours of proofing at 85 degrees.

- Lengthen the fermentation time: Whatever the amount of starter you're using, deflating the dough (preferably through stretching and folding) to give the dough more time to ferment will definitely increase flavor.

Of all of these, the 85 degree proof is, I think, by far the most important.Why is a higher temerature so important when other bakers recommend ordinary room temperatures or even refrigeration for the proofing?

zdenka

Sorry to revive this thread after so long of a period of rest. But I have a question. I looked for an email address but didn't fine one. Oh well...

You indicate that when feeding your sriff starter to add 1 unit of water for every 2 units of flour. But you did not indicate how much starter to use. You state early on to use 2 ounces of 100% starter to 5 ounces flour and 2 ounces water giving you 9 ounces of starter. How much of that start is used for the next feeding? All 9 ounces increasing the whole starter to 12 ounces? Or a portion like 2 ounces and discarding the other 7 ounces?

Like I said, sorry to be a pain and revive this thread. Thanks.

Sorry to revive this thread after so long of a period of rest. But I have a question. I looked for an email address but didn't fine one. Oh well...

You indicate that when feeding your sriff starter to add 1 unit of water for every 2 units of flour. But you did not indicate how much starter to use. You state early on to use 2 ounces of 100% starter to 5 ounces flour and 2 ounces water giving you 9 ounces of starter. How much of that start is used for the next feeding? All 9 ounces increasing the whole starter to 12 ounces? Or a portion like 2 ounces and discarding the other 7 ounces?

Like I said, sorry to be a pain and revive this thread. Thanks.

I could not find the answers to this question. Can anyone help? Thanks in advance ...

JMonkey's experiences and findings parallel my own closely. I use white rye flour as a sour note director when needed. One interesting point that's beginning to emerge is that low temperature starting aids oven spring. Clocehing the bread in the beginning retains steam but also lowers the rate at which the dough absorbs heat allowing a longer period of yeast activity and gas expansion. I had the same experience without cloching when the oven wasn't ready but the bread went in anyway. The spring was nearly double to what usually occured. Turing the oven up as the bread bakes to obtain the right carmelization of the crust is without question. It's just the initial conditions that are important. Come to think of it the old steam injection method injected water which lowered the ambient temperature of the oven. I believe that this is what we've actually been experiencing. Below is an example of my standard bake. The loaf is, by necessity, becoming larger due to the rate at which it disappears!

Wild-Yeast

Very nice expansion Wild-Yeast. Is that a sour dough Italian inside? I'd be curious to see the crumb if you have it.

Was the loaf pictured above covered or steamed?

Eric

Thanks MiniO.

Eric, It's a sort of mix of types. We like toasted bread and sandwiches resulting in a smaller crumb with a rich velvety texture somewhat similar to cake. It's very similar to Italian bread but has similarities to French. It has a sourdough smell but a distinctly sweet taste (strange I know). The loaf pictured above was baked on a stone covered with a stainless steel steam tray pan for the first 15 minutes. I preheat the oven to 450 F. using convection mode; parchmented dough is slid onto the stone and covered with the steam tray pan; the temperature is reset to bake at 400 F. The cover pan and parchment are removed after 15 minutes and the oven temperature increased to 450 F. Baking continues for 12 to 17 minutes longer, just enough to brown the crust but not long enough to bake too much moisture out of the crumb.

Wild-Yeast

I keep trying sourdough with not much success. Mostly my sour is not too sour especially since I lost my Ak sourdough. They don't revive well. They're not sour. They will not rise a loaf of bread. When I whip up a no knead recipe which is essentially a preferment with 1/4 tsp of yeast it comes out really nice. Large, flavorful and pretty with holes. I rarely make a fast rising bread anyway. I did once. People liked it. It seems so odd after slow rises. I have a few more things to try. I better get cracking. Oh I just realized something. I use to use Guisto's bakers preference thing. Everything came out great. I am using Pendleton Super Power Bread Flour and Various AP flours. I guess I best be changing back. I love Guisto's. It's so sweet.

mredwood, not sure why your starter is not producing sourdough bread. Are you saying the starter does not revive well ?

What exactly have you tried in terms of trying to revive it ?

SD starters ferment naturally all by themselves ( with feeding) so I'm puzzled that yours won't revive ?

This may help in some way: I am currently using my first and only SD starter which started 6 weeks ago with nothing more than flour and water. Its been working very well producing great SD loaves which take 10 hrs to double at cool room temps, then I cold retard overnight. Once at room temp again the next day they take a further 4 hours to complete 2 risings and foldings in warm temp. Thats quite a long time I think but the thing is, it works and the loaves have great crumb and sour flavour. I am just beginning a three day regime of feeding my SD starter at 4 hourly intervals during the day, then I will leave it overnight at the end of the 3rd day and then use my starter to make SD on the 4th day.

I believe this is going to optimise my starter and I expect very much quicker rise and proof phases. We'll see if it works... ! I'm not too concerned about hydration levels right now, only that I end up with a fairly dryish starter at the end of this feeding regime. I will learn more about hydration as I progress in my baking and reading up here in this forum.

My buddy who is a very experienced pro baker says it will work. In fact he says the starter when treated like this, performs much closer to instant yeast. I'm not sure about SD flavour though.

Let us know what those steps were to revive your starter.

Paul.

Thanks for your input. You are probably going to want more info than I can give. Here's what I do. Out of the fridge I take the crock. Open it air it out. After an hour or so I add flour & purified water to maintain the batter like consistancy I like. Ok I'm going to take it out now. Ok it's out. The culture always bubbles and smells good or not much at all. When it slows down I add more. Bubbles again. Not bad so far. Then when I am ready to bake it will be bully starter that I add per the recipe I am using. This is where things slow down and possibly change smell.

I guess my rooms are always on the cool side. I will expect that the dough developement will take longer now. But as it continues to rise the smell changes. Sour yes. But not the nice sourdough I like. An odd sour. Like too sour that you want to add something to mello it out or change it. Not plesant, odd. Not spoiled.

Usually after a time I give up and add a small amount of instant yeast.

Well another day another loaf. This science is understandabe as I read it but putting it into practice leaves a bit to be desired. I wish there was a simple rule to memorize. Like in planting. Fuzzy but down. Like cold or flu? Neck up cold.

Thanks again

Mariah

It seems to me that you may not be feeding your starter enough and that is why it is not raising your dough.

This is the method I have used for several years, both for the starters I developed and for others that people have sent me.

FOR FLOUR BASED:

1. Put one teaspoon of starter in a clean container. Add four teaspoons of flour and 3 teaspoons of filtered (non chlorinated) water. Stir well.

2. Repeat the above at 12-hour intervals, discarding the excess. I do this at 6 am and 6 pm as that suits my work schedule.

If you flush the excess down the drain, use plenty of COLD water. Also wash your utensils and containers with COLD water. Remember, the paste you made as a kid was just flour and water!

3. When the starter is nice and bubbly, you can start building up to the quantity you need for your recipe.

4. Use this ratio: one portion of starter, 4 portions of flour and 3 portions of water. Example: ¼ cup of starter, one cup of flour and ¾ cup of water will give you more than a cup of starter, which is what a lot of recipes call for.

Others use the ratio of 1/2/2 or even 1/6/6. But the 1/4/3 works for me.

5. After you remove what you need for your recipe, feed the starter again and refrigerate.

6. I usually start feeding on Thursday evening for a Saturday bake. That way I know my starter is good and healthy.

Another thing you can do with the excess starter is store it in a large container in the fridge and use it for sourdough biscuits and pancakes. Waste not, want not!!!!

IF YOU USE A SCALE, USE EQUAL WEIGHTS OF STARTER, FLOUR AND WATER.

Like I said, this has worked for me very successfully. You might also check my site at www.allthingsbread.bravehost.com to see if there is anything else helpful to you.

Bob

okey dokey I am going to do it. Now, Today. This means it should be good and going in a few days. We shall see. Thanks

Mariah

I too have been baking sourdough only since the beginning of this year and with moderate success. The loaves have not been especially sour. But recently I bought a copy of BBA and tried the Poilane-Style recipe. It does take up to 4 days.

Day 1 - create a barm from standard wet seed culture. let it become active and refrigerate over night.

Day 2 - create firm starter from barm - let it double in size and refrigrerate over night

Day 3 - make final dough - let it prove, shape as required, rise, refrigerate over night.

Day 4 - bake

The result was very sour indeed, probably due to the extended fermentation times. I've never tasted any sourdough (mine or commercial, UK or US) as sour as this.

You can cut out some of the over night refrigeration, for example bake on the 3rd day.

Very interesting thread and history. I want to go in the other direction -- my starter makes good bread that is excessively sour for my taste.

What I think I have learned from reading this and other threads and comments is that what I need to do is take my starter -- out of the refrigerator and build it / renew it 3 times a day for 3 or 4 days and move to a high hydration starter 125 %. Then make my bread and do not retard it over night but plan on baking the same day.

We will see how I do.

Dave

Yup, that should do it. My earlier attempts were "everything in a day" and they were decidedly less sour. Even I don't know if I want my bread quite as sour as I described above.

As I understand it, cold encourages growth of the sour aspects, warm encourages more of the lactobaccilli. This is clearly not the scientific explanation, but I'm sure you can find that on this site. I keep my starter on the counter and discard daily all but a slight skimming in the bottom. It's 100% hydration, and in this summer weather is ready in 4-5 hours. I can use it or just continue to refresh. I try not to put it in the refrigerator because I don't enjoy the sour as much as the complexity the starter adds.

Patricia

I followed several of your tips, including stiffening the starter, spiking with rye, and increasing my refrigerated phase. Been using the Basic Sourdough recipe from BBA and a starter initialized with Beth Hensperger's recipe from the Bread Bible.

My most recent loaf had a secondary fermentation in the fridge for 48 hours, and the loaf is as sour as anything I had in San Francisco.

I'm fairly new at baking and glad to see there are several on this site, just like me. But, I'm even more happy to read the pearls of wisdom from the more experienced bakers out there. A special thanks to "The Sourdoug Baker", your website is fantastic--a bloody goldmine with huge, priceless nuggets that would take me many years to learn on my own. My approach to making a sourdough starter has certainly been less scientific than most who've published their baking histories. Living in Oklahoma, a lot of the pre-San Francisco sourdough started here before it made its way out west. Being blest with a gregarious and engaging spirit--some, hopefully few, might call it being a pain in the arse---I've been able to talk with the simple, country folk who enjoy baking bread from sourdough starters that have been passed down from one generation to the next for well-over 70 years. What I've learned is what I like to consider just common sense. I start with the premise that wild yeast is what these hardy types had to use, not so much because it wasn't made at the time, which it probably was, it's just that most of these people were so poor they couldn't afford to buy it. I'm thinking here of a historical visit to a place on the western side of the state called "The Sod House" which was typical of the early settlers in Oklahoma and in my review of the possessions on hand, I could find many Mason and Ball jars, but not a single thermometer or digital scale or convection oven or steam injected oven, either. But, I know from eating at many a home out that way over the last 60 plus years, that these people could make a terriffic tasting loaf of sourdough bread.

From what I can tell, their starters were almost exclusively made from wild yeast by either leaving their jars exposed to the natural air-borne yeast that is everywhere around us, to adding the peels of fruit to induce the yeast to grow and then removed. Water was typically from well water which was full of taste imparting minerals and usually had to be left on the kitchen counter to warm to room temperature. The grains were wheat, maise, rye, millet, sorghum, buckwheat and the like. Those grains with "tooth" as I call it---meaning a strong taste when eaten raw were used more often than not. Also, since very few of these people had a/c, since it wasn't invented yet, it wasn't always possible to find a place that had exactly this warm place or that cool place to let the yeast do its best to ferment the grain with the aid of the liquid. But, one thing is certain, these simple, not particularly scientific methods worked. Sourdough has been around for a long, long time. So, I'm grateful for all of the wisdom that are contained in these many posts that go back for 3 or 4 years, I think. I like to think that maybe a great loaf of sourdough can be achieved fairly simply as well as with all the modern high tech that modern bakeries can muster.

With my own sourdough starter, which some how instinctively I knew to grab for the rye flour because the sourdough's I've tasted had been rye---made sense to me. Although I didn't measure proportions, my digital scale hadn't been delivered for many days later, I somehow lucked out and used "about" a 50/50 liquid to flour mix. When I put this together initially, I even added a tsp of commercial yeast because I thought that might kick start the fermentation and added a 1/2 tsp of honey to help the yeast on its way; yet another time I added barley malt. Yes, until I discovered that the yeast works fairly quickly generating its gas by-product, I had my fair share of overflowing experiences. But, I noticed that a nice, pleasant and earthy aroma was eminating from the ceramic yellow beehive container that formerly housed honey on my parent's table when I was growing up. I didn't realize this was supposed to be a tight fitting lid. But, I've kept it in there for the last 2 or 3 weeks and it goes from fridge to kitchen counter to sitting outside with the lid off to catch some of the natural yeast. If the top skims over because of the wind, I just spoon it into the mix. It works quite well, at least it works for me. Also, I haven't stuck exactly to rye flour, either. I've added whole wheat, white bread flour, spelt, and am now back to rye because that seems to produce the pungency of my recollection of what sourdough is supposed to taste like. Also, I've added buttermilk, beer, distilled water and tap water and they all seem to work quite well. The buttermilk probably provided the best fermentation thus far; but, the Guiness added the best aroma. But, I do not keep records and I grab what seems good to me at the moment. So far its worked.

My biggest problems were in trying to determine how much of the starter I should use to start making bread. One source very wrongfully said to use 1/3 of a cup; and my dough just seemed to sit there for the longest time before anything rise. I now use a cup of my very sticky and somewhat liquid starter which I always add to a cup and one-half of flour, usually whole wheat. I think all of you refer to this as the "preferment". This works really well for me and I simply add my starter to the 3/4 cup of water that I use to make the preferment-starter; the flour goes next and I stir by hand until its all incorporated into a nice consistency. (Once my starter was quite thick and I found that I could actually divide it into several little cubes and mixed those with my standard 3/4 cup of water--usually warm from the tap, but not hot.) Next, I let this prefirment sit on the counter where I can occasionally watch it to make certain that the fermentation process is working. After a couple of hours, or so, everything goes back in the fridge to slow the fermenting process down which I believe is necessary to build the taste and structure that is the heart of sourdough bread. I might leave it for a day or a couple of days--the longer the better if you want a stronger taste.

When I think the preferment has developed the taste that I would enjoy, I take it out of the fridge and let it reach room temp. When this happens it's time to add the remainder of my bread flour which today was some red hard winter wheat berries that I milled up in a new Nutrimill and the same wheat I got from the state wide co-op annual meeting yesterday. I mixed that flour with some KA bread flour and some salt (1 tbs) and stirred it in till finally I opted to use the Professional 6 qt. KitchenAid that was sitting on the counter next to me. Watching the dough knead, I decided add some olive oil and honey to the mix which also required some extra flour. I finished kneading while the dough was still tacky, not dry and not sticky. I was guided by the principle that whole grain wheat bread needed more liquid to break down the cellular composition of the wheat berry, especially since this was hard red winter wheat. I then did a little hand kneading, just for the fun of playing with the dough---I'm sure all bakers must do this because it's such a pleasurable experience--when living in Santa Rosa, CA, I think my friends would call it a "Zen thing".

Next the dough sat for two hours, proofed or rose beautifully; I cut it in two fairly equal pieces and made a french loaf of one and a large boule of the other. I put the french in a clouche (is that spelled correctly?) which I got at the end of last week; and the boule went into an enormous cast iron dutch oven which was sprayed with olive oil-lightly. The clouche or ceramic baker, I simply put a 1/16 inch layer of cornmeal. After letting the dough rise till it was slight less than double, about an hour, I put both cooking utensils in the oven.

The dough was not dumped into a hot cooking utensil--mainly because I tried it once before but found the cornmeal or oil had burned up by the time the utensil reached 500 deg. Maybe I should have added the corn meal just before adding the bread dough. However, by the time I would have gotten the cornmeal and the dough into the clouche, my oven would have cooled off and I probably would have burned the hell out of my arm or hand. I let the dough proof in their cooking vessels at room temp and preheated the gas oven to 500. I cooked the bread at 500 for 40 minutes. This may seem long, but remember, I started with a cool oven. At about 37 minutes I could first start to smell the bread baking, Ahhhhhh, and then turned the oven down to 350 and took the lids off both utensils and let cook for another 15 minutes. I forgot to score the loaves but that didn't seem to bother them as they both rose quite a bit more in the oven while cooking, but did not split open.

One loaf went to my neighbors with a newborn and I kept one. I have pix on my camera, but I haven't downloaded them to my computer and I'm not certain how to upload them to this thread anyway. I just want to add one last thing. I'm not a professional baker, that's obvious. I bake bread for a couple of reasons, to eat and the fun of it--that's it. I like variety in what I eat, so I may make a sourdough whole grain rye one day and a few days later make a cibatta or a levain the next. I always, always, always throw in different grains or whatever just to see how it turns out. It might be a cinnamon raisin, a honey-whole wheat. The point I'm trying to make is that I'm not looking for consistency as I'm sure the commercial bakers are trying to do. I refuse to agonize over a loaf if it isn't perfection--but less than perfection has always tasted good, at least to me. And that is where the second reason I bake comes to play---I do it for the sheer fun of it. I like to cook, baking is part of that process. Perhaps a better way is to say its part of that journey that I'm making. It's neat for me to know that I'm using, at least with my sourdough, processes that my great grandmother used when I was but an infant--and I'm 64 now. So the historical and ancestral thing is kind of a kick for me. Plus, I get some neighborhood kudos which is nice because they always reciprocate with something tasty. Anyway thanks for letting me add my musings. BerniePiel

Since you referred to the "western" part of the State, I am assuming you live in the Eastern part of Oklahoma.

I live about 20 miles South of Tulsa.

If you are anywhere close, give me a holler and maybe we can swap starters and recipes, etc.

And at 64, you are a mere pup - I turned 74 this week.

Bob

oldcampcook (at)yahoo.com

Hi, I am so glad to see these posts, I've learned so much and am so excited! I can't wait to get loaf #5 rising...

Just for fun, I decided to keep a second starter going (to keep Ralph company on the counter) which I am feeding as per usual except with buttermilk instead of water. I wanted to see if I could get it to work, and whether there would be any additional sourness.

Am I about to commit total heresy? If so please say; do not send the sourdough police after me tho, please!

Gabrielle

HI GABRIELLE,

I USED BUTTERMILK IN MY STARTER, AS WELL AS, GUINESS AND DISTILLED WATER. I DID NOT FIND ANY THING HARMFUL ABOUT USIING ANY OF THOSE. INDEED, IT WAS MY GRANDMOTHER'S RECIPE FROM AT LEAST 70+YEARS THAT WAS USING THE BUTTERMILK. THE GUINESS WAS MY IDEA AND IT PRODUCED A REALLY WONDERFULLY AROMA ON THE SECOND DAY--NOT SURE WHETHER THE MALT, HOPS OR WHATEVER CAUSED IT. BUT, IF YOU ARE NEW TO THIS SITE, YOU WILL FIND MOST OF THE PARTICIPANTS ARE EXTREME IN THEIR MEASURING AND RECORD KEEPING AND GADGETS. I JUST WANT TO MAKE VERY TASTY BREAD AND DON'T MIND MAKIING A MISTAKE IN MY EXPERIMENTS. HOWEVER, THAT SAID, I DO SEEM TO HAVE READ THAT THERE ARE NUMEROUS SOURCES FOR YOUR LIQUID, INCLUDING VARIOUS ACIDIC FRUIT JUICES, E.G. PINEAPPLE. SO ENJOY THE BREADMAKING JOURNEY AND EXPERIMENT THEN LET THE REST OF US KNOW WHICH WORKED AND WHICH DIDN'T. HAPPY FLOUR TRAILS.

BERNIE PIEL

Thanks, Bernie. While I wait for my kitchen scale to arrive (I'm in Canada and had trouble getting the one I want), I have been getting familiar with adjusting volumes by the look/feel and judging the amount of oven time. I'v been unable to work for 5 years, so this is the perfect 'pre-occupation' for me - I can wait for proofs, it's not physically demanding and a hot oven chases away the chill. Oh, and the end result is so exciting!

Thanks for the open arms...

Gabrielle

Gabrielle,

I think the following site would be very helpful. http://www.youtube.com/user/foodwishes#p/search/0/6rvz0WKanGU

He is a food program producer and from what I can tell, just loves to cook, teach, promote food. In the referenced link he teaches how to measure flour. Seems simple enough, doesn't it. But, I learned I had not been measuring properly all these years and this most likely accounted for the numerous times my ingredients were too dry. From this link, you can go to numerous other links for various instructions including a really good one on No Knead Ciabbata which I did over the weekend--very good results. Let me know what you think. Bernie Piel (berniepiel@cox.net).

BTW, after seeing this episode I bought a digital scale and am sorry I didn't do so much earlier, ditto with a thermometer which sure removes the guessing of when to pull a loaf out of the oven and lots of other uses.

Happy Flour trails.

Bernie Piel

Thanks JMonkey. As a neophyte and after much research I come across your thread on a stiff starter and a "sour" bread taste. 2 for 1 - what luck!

As one who disdains using scales, I'm a kinda of about here sort, and prefer using volumes and the feel of the dough, which for me is the artistry of bread making. Much can be learned from mistakes of how your flour should feel. I watched my grandmother making biscuits and breads and she used an enamel wash pan large enough to hold her flour and liquids and worked them to the proper consistency. I've watched many Italian ladies using the well method also and thus my fascination.

Plus, my uncle was a professional baker for 60 years and used weights for the commercial apllication. I certainly did eat my share of doughnuts, cakes, biscuits, and breads growing up. As I think about it, much of our butter and milk products were either churned and produced by local farmers. We never used unsaturated oils either as we rendered our own "lard". I guess I was "organic" before it became a word in our lexicon.

I have enjoyed reading the many articles on this forum from knowledgeable and experienced bakers, using the technical and scientific approach, so that I might understand the process. I too, come from a technical background, but have chosen not to use that approach.

You did provide some details for volume information for the hydration percentages. If you don't mind I've worked up some weights by volume for both water and flour. Of course these are approximates.

Water Weight by Volume

1 Cup = 16 Tbsps

1 Cup ≈ 8.35 oz

1 Tbsp ≈ .52 oz @ 70°F

1/4 Cup ≈ 2.1 oz @ 70°F

Flour volume vs. weight chart: (Sifted Weight AP Flour)

Cup Gram Ounce Pound Kilogram

1/4 31g 1.1 oz 0.06 lb 0.03 Kg

1/3 42g 1.5 oz 0.09 lb 0.04 Kg

1/2 62g 2.2 oz 0.13 lb 0.06 Kg

2/3 78g 2.7 oz 0.70 lb 0.07 Kg

5/8 83g 2.9 oz 0.18 lb 0.08 Kg

3/4 93g 3.3 oz 0.20 lb 0.09 Kg

1 125g 4.4 oz 0.27 lb 0.125 Kg

1 tablespoon of flour = approx. 8g or 1/3 oz

3 tablespoons of flour = approx. 25g or 1 oz

is to add one slice of your already made sourdough bread.

Take the perfect slice (ends with crust even better) run it quickly under potable water and crumble it into your just refreshed starter to ferment with it. When the starter is ready, use normally.

This kicks up the acid and flavor index! Try it :)

How does this work? Baking effectively kills the yeast. Am I missing something here? Yeast dies at 125 deg. F.

Mini,

That is a great suggestion that I'll soon try! I am one who loves a good tangy bread, but am unable to get a finished product to my liking.

I have also experimented with different hydration levels, and high and low temperature proofings without much success. The added slice may just be the secret, thank you for that bit of information.

I'd like to try this with my rye breads also. I know that altus is suggested in the mixing of the final dough, but I don't recall ever seeing anything about adding it to the proofing of the starter.

Thanks again for sharing your bits of wealth with us!

She brought it up for examination! :)

I confirm it is being done and it is just the sour I've been looking for.

Mini

My apologies to Christina!

Mini, you wrote to run the slice of bread under potable water before crumbling. What do you suppose would be the effect if one were to use milk in place of water? As you know, sour milk is the result of lactic acid. Do you think this would be a big shot in the arm for the starter as far as sour creation? Just a thought.

Try it and see. I've never put milk in my rye bread. I have put rye into my milk bread.

This is a bit aside, but in the beginning of my experimentation I made a starter using buttermilk instead of water while I waited for my culture to get sour. It was great, I really liked it! I understand you can use lots of other things too, like beer etc.; I haven't done this myself...

It's been several weeks since I posted anything because I didn't think I really had anything to add, until yesterday. I made my first batch of "San Francisco Sourdough" [made using Peter Reinhardt's formula found on page 64 of the text "artisan breads every day". To me that is a euphemism for any sourdough bread that is made from plain bread flour, salt, water, and a sourdough starter. This was not Sourdough Rye or whole wheat. But, here's what I think is important that I'd like to tell you about. I made a new starter from scratch as I had let my old starter sit on the counter unattended for nearly one week and saw that it had developed some rather ugly and hairy mold. I pitched all of it. The starter was somewhat more liquid, than solid. So faced with a new challenge of creating a new starter, I read several of my bread books to see what the consensus was on how to go about starting from scratch.

Now I'm not the most patient guy in the world, so after reading that one should start with a quarter cup of flour and so much water and pineapple juice from one expert and just 1 cup of flour and water from another expert, etc., etc., ad nauseam, I decided to see what would happen if I just took equal amounts of KA Bread Flour, in this case, 1 cup, and the remaining cup of liquid comprised of distilled water and, since I had no pineapple juice handy, I opted to use 1/3 cup of blood orange juice and the remainder of 2/3 cup distilled water. For those not familiar with Blood Oranges, they are somewhat smaller oranges, somewhat larger than a clementine orange, fairly juicy with the most beautiful, deep red/blue color I've ever seen in a fruit of any sort. The juice is heavily pigmented, as well, meaning that later additions of water and flour did little to change that color until after the 4th feeding---then it dropped to an ever so slight purple haze.

But, starter color wasn't that important to me. It took three days of religiously feeding the starter before I noticed it had come alive with little bubblesl that I could see through the glass, but nothing on top of the mixture until about the 6th day. I remember Eric's video talkiing about how his starter was fairly thick and wouldn't pour---so I continued to lessen the water from the formula of 1 : 1. Thus my starter is quite stiff, almost reminds of wall paper cleaner--thick and gummy.

Also, after the initial 1/3 cup of Blood Orange juice, I never added any other juice to my starter. When I first put the spoon in the starter, I was quite surprised how thick and heavy it had become. However, I was using Reinhardt's recipe for San Francisco Sourdough and his calls for the creation of a starter sponge using 1/4 cup of starter mixed in water and about 1 3/4 cup of bread flour and 1/2 cup + 2 Tbs of water, mixed then let sit for approximately 6 to 8 hours. I followed this procedure only it had to sit for about 12 hours.

The next day I made the dough with the all of the sponge just created, 1 3/4 cup water, 4 1/2 cups of bread flour; 3 1/2 tsp of kosher salt. I allowed the dough to sit at room temperature for 2 hours then put it in the fridge for about 10 hours. The next morning I took it out and allowed it to sit for about 5 hours (PR says to shape it after 2 hours, proof for 2 hours then bake); shaped it into two baguettes and a boule. I allowed this to proof for 2 hours and honestly didn't see much, just a little, rise. So I was immediately suspect that my new found starter was going to be a bust. Well to make matters worse, I put the loaves in an oven to proof and sadly didn't remember to turn it off until I saw the temp guage reading 136 deg. Although I quickly pulled it out of the stove, the baguettes still had formed a skin across the top and the dough felt like a small water balloon. So thinking my baguettes were a lost cause, I pulled them from the oven and took them off the french loaf pan and put them on a marble slab that I was using. I took the boule and after seeing it wasn't quite as bad as the baguettes decided to leave it for cooking---and I lamed the boule. I then decided to just go ahead and put the mostly degassed baguettes on the oven stone--thinking I would feed them to the birds.

I was shocked when I watched the boule rise about 175% and the baguettes raised almost 125%. The boule was scored and I could see the boule gradually break tear itself open even though all loaves were scored. Well they weren't the best shaped baguettes, but I would stand these as some of the best sourdough I've created... I even have the pix.

Okay, I've refreshed my starter with the "magic slice" of bread. Now I would like to take the correct amount of this starter and mix it with my flour and salt to arrive at the correct amount of finished dough. Normally, I put this dough in a plastic food container, and wait a couple of hours or so for it to double. At which time I measure, form, and place in the banneton for the final rise.

I'd like to develop the tang in the bulk final dough. In the past, I've put the plastic container of dough in the fridge over night (8 hours or so), and it usually more than doubles by the next morning. The problem I've encountered with this method is that by more than doubling, it seems to have taken the energy out of the dough so that I fail to get good oven spring. It'll rise (final) in the banneton, but seems to lack strength to hold it's form and tends to spread out to the sides after going into the oven and I end up with a loaf about 6 inches wide and 2 inches high. It seems this is due to the over proofing while in the fridge. Should I remove it a couple times during the night and do a couple fold and stretches? So how do you gain sour and over proof at the same time, and maintain good oven spring at baking? Thank you.

I keep track of the flour and water, then add the slice or crumbs. The old bread is already salt balanced so you only need to figure salt for the flour in the starter. (This little bit of salt can slow down the fermentation.) If you measure while feeding, you know by the weight how much flour is in it. If you mix it all first and then measure, hmmm. Interesting.

You could try using less starter in the dough before the 8 hr fridge rise so that there is energy left. Try using the same amount as before and make comparisons.

Not quite sure of the question... You don't want to over proof. Folds are always good as long as the dough doesn't rip.

Mini

Mini,

The amount of starter that I was proofing to impart more sour used only 18% of the total overall flour amount in the recipe, and just enough water was added to make a 60% hydration level. So I was thinking that perhaps this was too small of an amount soured starter to sour the final dough before it doubled in a 2-4 hour period. Therefore, why not build the starter using say, 40% of the total flour amount? That way I'd have more than twice the amount of soured starter which should have a greater influence on the overall taste when mixed with the remaining flour. This way I can let the final dough double in volume in the normal 2-4 hours before shaping and final proof, and thus I don't have to retard the complete final dough amount which seems to exhust the dough of its rising ability. Perhaps the secret is in using a greater percentage of the recipes total flour to create the soured starter which imparts a greater sour taste, and at the same time the remaining flour adds enough energy to give the loaf the needed oven spring! I'm going to try it! Oh, no cup measuring here, only scaled weights:)

Well my latest attempt at gaining mouth puckering sour failed! Well, maybe not mouth puckering, but a noticable strong sour.Something that doesn't resemble eating a homemade version of Wonder Bread!

I've noticed that when I refresh my starters that I've had stored in the fridge for 10 days or so, they are very sour smelling. One good feeding and back to the fridge they go strong as always.

So for my next attempt I've taken some seed starter, refreshed it a few times to build it up both in strength and needed amount to contain 40% of the total recipe flour. I've placed this in the fridge to "cure" for 5 days or so at which time I'll use with the remaining flour and water to make my bread. So with any luck I should have a good ripe starter to add to the remaining flour to build strength, and provide me with loaves that display a strong sour taste.

This sourdough thing, ya gotta love it or it'll drive ya nuts!

might leave you with a weak 40%. Try using it sooner within 2 days. Give your final dough the retard instead and see if you can't get warmer dough temperatures during your active fermenting phase.

Save a wad of this dough to ripen and make a starter for the next loaf. See if that doesn't improve the sour flavor you're looking for.

Maybe someone has asked thisd question and I missed it - after proving overnight in the fridge, do you put the loaves straight into the oven, or let it come to room temperature first?

Isobel, Suffolk, England

If it's a sourdough, bake it before it doubles in volume.

If it hasn't risen much, let it come up to room temp and rise a little before baking.

Thanks so much for this post! My sourdough isn't very sour, and I didn't quite understand what the hydration %'s meant. But this post definitely helped with both, which I very much appreciate. I'm borrowing it for my blog as it's *the best* explanation I've yet seen online, all credit goes to to you. :)

The blog page

I have been doing sour dough for about 3 years now and I just found out to make a stiff stater I used about 1 cup of my water & flour starter in a different container Recycled Ice Cream bucket :-) I added 1/4 cup Flour 1/4 Cup Butter Milk and apx 1tsp sugar I do blive that if you are going to be doing a lot a baking you need more then 1 qt, of stater so i keep about 1 1/2 gals around plus about 1 PT. in the freeze just in case If you freeze the starter it does not need to be fed but will take a day or two to come back to life! Also after a while your starter will be your starter. It does not matter where it came from. On the Butter milk get the smallest one you can find in the store break out a qt jar add 1/4 C butter milk and the rest with regular milk put the lid on shake well put in a warm place and in 8 to 12 hours you now have a QT of butter milk. Store in the frig. do not worry if it looks a little wattery at first it will thicken up when chiled. At a fraction of the cost you can repeat the process over and over again using your butter milk and at around $3.50 a QT the savings can add up!

Virgule, I have been on the trail for a little while, there are many crossroads, switchbacks, and dead ends. I primarily use 100% home milled winter wheat, so my trials may not be of much help to you, but Debra is the expert, and her summary is here. https://brodandtaylor.com/make-sourdough-more-sour/ She does not address in that chart, but described in another post, is hydration of the starter. IIRC, she said a low hydration starter encourages the ratio of sour producing agents to be increased, but that once you have the ratio favoring that, you want a wetter starter to encourage production. What I have tried, with some hits and misses, is a refresh at low hydration, then a final refresh at 125 to 150% hydration. Another thing she does not address is the percentage of starter. From what I have read, the more starter you use in the final dough, the less sour - though I don't know if that is a byproduct of the fact that less starter normally means longer fermentation times. I have used very low percentages, down to 2% , with again some limited success.

Thanks Barry, I appreciate the shout out, but I want to clarify that that is not my summary nor my chart. It is Brod and Taylor's spin to employ a proofer, because they sell proofers. Low hydration doesn't encourage sour producing agents (LAB), it does the opposite. But it can influence the ratio of acids that those agents produce. Hydration doesn't guarantee any particular degree of sourness on its own.

My best,

dw

Debra, sorry, they listed you as a source, so I assume they had consulted you. Am I right that low hydration influences the ratio, and that higher hydration can encourage more sour, once the ratio is established? I thought I put that together from posts that you had written?

It's very obvious now that I've figured this out, and I find it strange that I have never read this explanation when people discuss "why bothering with a mother culture?". I would love to hear from experts on this "new" observation.

http://www.thefreshloaf.com/node/15657/sourdough-stages#comment-101215

Sounds like you're doing well with it. Stay observant and keep up the good work :)

dw

Hi Debra,

I've just spent 24 hours reading some of your posts. I can't believe you've been posting since 2009 and still going strong. I stopped when I realized there is no way that I can read them all, AND make some sense of it in the end. It's just too much!

I'm exhausted - and laughing: it seems the entire internet is your classroom. Looking at the hundreds of similar questions and problems, it also appears that we are eager but often confused students :-)

I would like to ask if you know of a place on the net showing a set of diagrams like those requested by one of your fans here: http://www.thefreshloaf.com/comment/103292#comment-103292

I realize now that It's almost impossible to describe what each person's specific conditions really are. Too many variables, too many aspects of that person's methods that are silent/assumed, and so much non-linearity in the relation between variables. So what could be a good advice for one person's situation could very well be the wrong advice for another person, even though they appear to be facing the same symptoms (but have different overall conditions).

I'm hoping that such diagrams could work for bakers the same way e.g. phase diagrams for metallurgists: different factories produce different steel, but they all rely on the same phase diagrams to determine how they go about manufacturing their specific products.

Thank you very much for all your contributions to this overwhelming site!

I realize now that It's almost impossible to describe what each person's specific conditions really are. Too many variables, too many aspects of that person's methods that are silent/assumed, and so much non-linearity in the relation between variables. So what could be a good advice for one person's situation could very well be the wrong advice for another person, even though they appear to be facing the same symptoms (but have different overall conditions).

You pretty much pegged it. The answer is always, "It depends ....."

dw

It's never that simple with living things.

Barry,

Yes, the author was one of my students, and she used concepts from class to design the processes for the two breads. She also asked permission to use one of my diagrams in her article, and sent me an advance copy to preview. But the words and tables are hers, and B&T doesn't speak for me is all I'm saying. A few points on sour vs mild were a bit misleading, but in the whole she did a good job making it work, as I said, to employ a proofer :)

Hydration can influence acid balance, and sourness, across the whole range, low to high, and so is never established as a constant. It is a myth that acetic acid producers are favored by low hydration and lactic producers are separate. It is the same populations simply changing what they do in response to the conditions they find themselves in.

It's also a myth that acetic is more sour than lactic. They taste different and so they each contribute to the flavor profile, but they can both be sour or mild depending on their overall concentration. There will always be more lactic than acetic in sourdough fermentation regardless of the exact balance.

My best,

dw

Debra, thanks for your reply. I feel like the blind squirrel, every once it a while I stumble into a very sour sourdough, but consistency is eluding me.

The flour has a lot to do with it, and not many can withstand a lot of acidity for very long without breaking down. White flours have less proteolytic enzymes, but not as much buffering capacity. Whole grains have more buffering capacity, but more gluten-destroying enzymes. It's a challenge.

For what it's worth, the San Francisco French bread process of old was traditionally done very warm, very firm, and with a high protein white flour. No retarding. The mother was fed at least 2, often 3 times per day continuously, never refrigerated. It starts with the starter.

Debra, thanks, I have played around with very warm - 92 degree fermentation of the starter, but that limits me to just the weekends.

Hi Barry,

92 may be a bit too high to maintain good leavening in a traditional San Francisco-style starter. 78-82 is probably plenty warm (and would have been more typical). Maybe up to mid-80's. It's hard to maintain an adequate feeding schedule unless it's your profession though. It's the firm dough, frequent small feeds and warm temps that seem to select for the characteristic microbial profile. 92 degrees should be okay for the final proof when you have the right flora. But if you don't, it might not rise for you.

Wish I had some better pointers. Starters are as individual as their keepers, so the best tip I can give is to just keep working at it :)