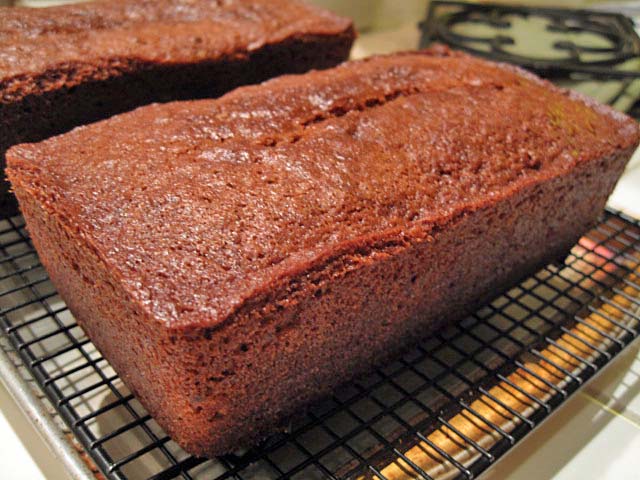

Large bâtard made using the formula for the SFBI Miche

This bake was inspired by the very large bâtards Chad Robertson bakes, but the formula is that of the miche we baked in the Artisan II Workshop at the SFBI last December.

- Log in or register to post comments

- 24 comments

- View post

- dmsnyder's Blog