This bake was made by combining two starters together namely spontaneous sourdough (type I) and sourwort (natural type II) in search of a more unique and complete taste profile along with good bread appearance.

The motive behind this test was based on the particulars of each one of the two ferments that I keep which possess very different but complimentary characteristics.

Sourwort, basically the hydrous outcome of natural anaerobic lacto-fermentation of malted grains at a temperature range close to 40C. These conditions discourage spontaneous yeast development and at the same time encourage native lactic acid bacteria to activate and produce mainly lactic acid and various other fermentation by-products that contribute to taste, dough development and subsequent yeast (wild and/or commercial) function.

Sourdough and because of the way I maintain it, lies at the other end of the spectrum. It is put to ferment at 18C aerobically, has a relatively stiff consistency encouraging the growth of yeast with robust leavening power and acetic taste.

You can tell immediately the difference between the two ferments by tasting them raw. One tastes more dairy the other more vinegary. Both aromatic each in its own sense. Here are some more in depth details of the two ferments used in this bake:

Sourwort

500g water ; 150g cracked spelt malt ; 1tsp a.c.vinegar 5°

Fermented anaerobically near 40C for 24hours. Then strained and letting its temperature fall gradually over the next 12-18 hours or so before transferring it to the fridge (I’ ve tried 10 days old sourwort straight from the fridge with success). I have noticed that by letting its temperature fall slowly until it reaches 18-20C it enhances its characteristics, probably by allowing other temperature specific bacteria species to be activated and contribute overall.

Sourdough

This is a spontaneous type I sourdough starter, maintained by feeding it once a day with organic whole rye flour, inoculation rate 50%, hydration 75% and fermenting temp 18C. Maybe once a day I would give it a good stir either because I use part of it to bake with or deliberately to promote aerobic conditions.

To sum up, by combining these two different natural starters the final dough contains fermentation products and by-products produced/collected over a very wide temperature range, all the way from 40C down to 4C when final dough is retarded for nearly 20 hours to proof. And it is exactly this wide temperature range that engages a broader microbial species number to get involved which in turn (I hope) will grant bread superior and more unique taste as compared to traditional methods using single preferments. And as far as structure is concerned, sourwort (apart from other factors) certainly contributes positively to openness/airiness/fluffiness of the crumb as it has been shown elsewhere.

The bread in the photos was made using these ingredient percentages:

304g RobinHood AllPurpose flour (p=13.2%)

16g Prefermented rye flour (sourdough 5%)

Overall hydration 75% ; sourwort 10% ; salt 2%

Plus soaked and strained bran flakes 4%

The Method

Involved a 3 hour extended autolyse of all the unfermented portion of flour with 65% hydration at 28-30C followed by mixing in the rest of the ingredients. Bulk 04:30 at 28-30C with lamination and folds (when needed) during the first 3 hours. Shaped and retarded (4C) in banneton for ~20 hours. Baked in DO as usual.

Taste

Well this is the most difficult part for me since English is not my first language but I’ll try. The taste came out as hypothesized having complexity and a variety of nuances from the stiff rye starter, presence of the lactic liquid and long autolyse. The characteristic spelt malt taste shows through in a pleasant way (makes it taste bready). Gentle sour after taste with a tad of sweetness. Definitely unique. These preliminary results encourage me to try it again, maybe with different flours, increased hydration for a more holey crumb, rye malt sourwort and what else pops in mind. Till next time…..

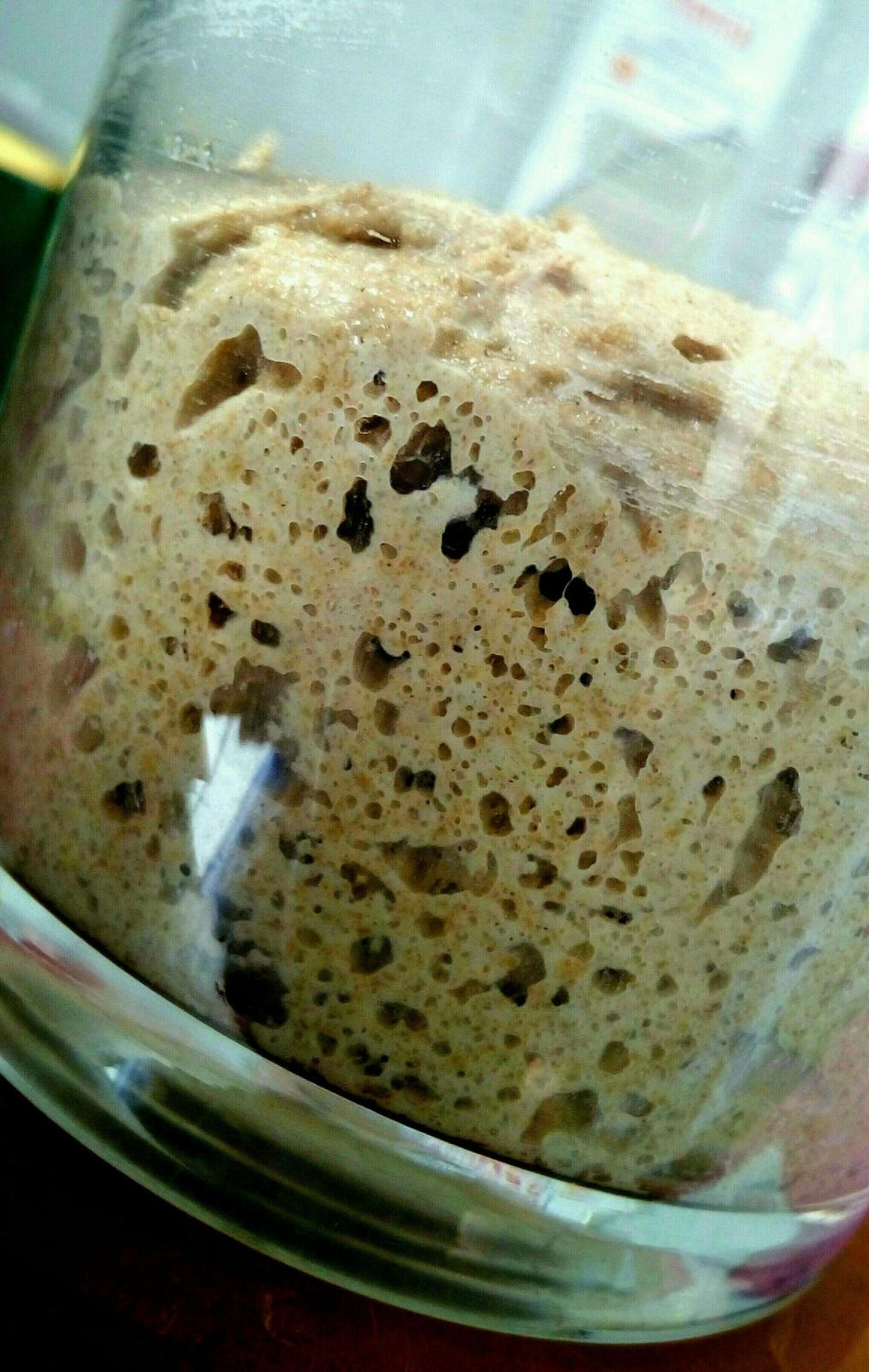

The rye sourdough type I

Spelt Malt Sourwort. Nothing much to see really, just liquid.

Spelt Malt Sourwort. Nothing much to see really, just liquid.

- PANEMetCIRCENSES's Blog

- Log in or register to post comments

Thanks for posting. I find your posts really inspiring! The loaf looks great.

Thank you Garry. Your early comments are always wellcomed and anticipated. Thx.

Dabrownman (you rarely see him here these days - I hope he's doing ok) was of the opinion that the best bread has a balance of both lactic and acetic acid. Which is exactly what you have done here. Such a lovely bake. Thank you for the very detailed description and instructions together with your thoughts on the whole process.

Questions... Can I use my type I starter to develop a type II starter instead of making a second starter from scratch? I.e. can it be done in a feed or two just by altering the technique? I imagine because my type I starter already has the bacteria capable of a type II starter all i'll need to do is maintain it in a way to encourage the lactic acid bacteria over the yeasts. Then I can feed my sourdough starter as usual and use them both in a recipe to replicate what you have done. Logically I would think it'll all be in the temperature and hydration.

Hi Abe, I can’t thank you enough for your comments on this bake.

From your posts I presume you are a dedicated and successful, long time sourdough home baker. I also presume your sourdough starter is quite old (the older the healthier, unlike us humans unfortunately…) This means to me that it already contains a very strong and well established colony of microbes, naturally selected and grown under the conditions you usually keep your starter.

There are lots of reliable articles around explaining how one can change the character of an existing starter, tilting the balance either toward acetic or lactic production with fairly simple means and patience. By altering hydration, temperature and feeding schemes and even flour. This is something you can surely do haven’t you done already and experiment with a discarded portion of starter just to be on the safe side. You can always keep two starters one liquid one stiff (specific hydration levels don’t really mean much to me as dough consistency does since this is the real environment microbiomes have to live in and metabolise rather than “reading” somehow the hydration level and acting accordingly, that would be spooky!)

The bacteria established in your starter are obviously the ones selected naturally under a given temperature range. I don’t think they would be very happy at a much higher/lower temp than that they naturally managed to prevail over others. How productive an Eskimo would be working in Sahara desert? J and vice versa.

Making sourwort on the other hand sets the stage from scratch selecting those microbes native to malt grains that flourish under warm conditions (near 40C). Those warmth loving bacteria are presumably absent/atrophied in your starter. Where are they going to appear from when you raise the temperature or water content of your starter? You will have to provide a source for them.

So either keep two sourdough type I starters (one lactic one acetic) or make sourwort from scratch. Don’t be intimidated, it’s really as easy as making filter coffee.

CLAS is another similar possibility. That’s where it all started for me being introduced to RusBrot by Ilya Flyamer and Yippee reading here at TFL.

Disclaimer

Please note that I am not a qualified person to speak about these things. My thoughts only come from lots of reading, intuition, scientific but different background and experimenting (playing around really) with home baking as a hobbyist over the last 10-15 years or so. Forgive any wrong advice possibly given.

Makes a lot of sense. Explains why our starters differ so much. We all live in different climates and feed different flours so our starters, even if they're all type I, have selected the microbes that behave best when we made them. That[s why some perform better in cooler climates, and vice versa, because the microbes able to take hold were selected under those circumstances.

After reading what you have written I agree it would be best to make a type II starter from scratch. My next project. First i'll need a way to control temperature. In the meantime i'll source some malt.

Really lovely bake. Enjoy!

Not sure how you can improve upon this bake and that beautifully open crumb. I think it is spectacular already. Very nice bake and thanks for sharing your methods in creating the two preferments.

Benny

Thank you Benny. I think that bakers and artists/painters share one common thing between them. They all think that their next work is going to be their masterpiece. Allow me to dream and hope. Thanks again.

Nice looking loaf once again. Your method is interesting as always. As I understand it the objective was to create a best of both worlds bread that was more fully flavored by combining a sweet and sour sauce approach. So how was it? Did you get a nice balance or more nuanced flavor than the dry yeast/wort version?

Don

I would like to thank you up front for the very useful and helpful comments/suggestions you made in my previous post. First I baked a more ‘normal’ loaf size. Second I changed my old and worn out banneton which I had to dust heavily to avoid stickiness (no more powder donut looks!). And finally I posted to the blog section this time. Much appreciated.

Now for this bake. Obviously the double starter technique used here produces a more complex and deeper flavor profile as compared to the yeast/wort version. Not that the latter lacks taste. That too has a pleasant and gentle sour nuance since in this case (absence of sourdough) the amount of sourwort used can be increased. And also the production speed is much faster due to the use of commercial yeast. As you are surely well aware of, making bread is a vast field open to so many options and variables. And ‘taste’ is another such vast area very subjective. One person prefers ‘this bread’ the next another (something like music pieces really). My draft personal taste-list (better first) would probably be: (i) double starter (ii) yeast/sourwort (iii) yeasted preferment (iv) plain yeast.

Thanks for your interest

Savvas

I don't know why. I created a new batch of sourwort, scaled the recipe to 200g for my tiny pan, and otherwise followed your plan. My sourwort pH was 3.3 and my sourdough starter pH was 3.8. The SD starter was doubling in 3 hours.

The dough rose by 50% in the first rise, then I shaped and panned it and into the fridge (3C). 24 hours later it had risen none at all. I took it out and kept it at room temperature 25C for 3.5 hours. During that time it rose to about 3 inches tall (an inch below the top of my pan). I baked it as usual and produced a 3 inch tall loaf that looked and tasted very strange. Note the strange white top; I did not flour the loaf. The sides are pale brown and the top is very white. The pH before baking was 3.3 if I remember correctly.

200g of flour usually produces a 5 inch tall loaf for me.

Any theories on what went wrong?

Despite its obvious defects I like the appearance of the crumb structure. Uniform distribution of alveoli just the right size for my likes of a sandwich slice. Could have been a great pan loaf if some things hadn’ t gone wrong.

Your sourwort too acidic. I would prefer it having a pH near 3.7-3.8 (that’s a big logarithmic difference from the number you mention).

Seems like a skin has formed on the top of your dough at some stage. Cooling conditions? Condensation? Not proper covering of the dough? Too long exposure to air? Don’t know, can only guess.

Usually retarded doughs don’t rise much in the fridge if any at all. Avoid retarding your tin loaf. Better give pan breads a full bulk/proof at warm (27-30C) conditions and bake same day. Fluctuations caused by retarding before vigorous fermentation was given a head start and then continue with warm proofing, all these are bad practice and will never give you the desired results. Your dough seems mistreated in that sense. Go gentle with it and follow the flow, consider your dough as a human baby rather than something lifeless to be thrown here and there and expect it to be happy and smile back to you!!

But still I think you’re on the right track not far from ideal results. Just focus on your dough handling techniques more than ingredients used.

Best of luck, Savvas.

Thanks

gb

There is a worldwide accepted doctrine that bread making is half science half art. I’m not talking here about commercial bakeries with well-established production lines and hundreds of identical loafs baked day in day out.

The art part goes hand in hand with instinct as well, ‘baking instinct’. And how is this developed? Simple, by watching the experts how they do it and trying to mimic them by baking many times a week for long periods of time. And also registering in mind how different doughs respond under different processing schemes and conditions and combinations of all these. In other words a very long and never ending learning curve. But eventually I think the sunny day usually comes when one is able to orchestrate all the different bits of knowledge and experience gathered on the way and make nice bread at least most of the times. Oh, and as if all that wasn’t painful enough ‘positive thinking’ is also a must prerequisite.

In my experience bread recipes are not to be copied exactly to the letter but simply taken as general guidance. Using a recipe as a starting point one can then manipulate it and test it in his own environment several times, tweaking things, essentially ending up/creating his own personal recipe. It’s a lonesome process. Ok, end of mumbo jumbo and back to planet earth!

Cutting the much acidic sourwort with water doesn’t make sense. It is not actual ‘pH’ you’re putting into your dough but a microbe colony with its fermentation products and byproducts.

Putting such a small piece of dough (as you say sitting at the bottom of the tin) probably not fermented enough before at the harse environment of 3C is not a good practice. It will cool down fast, yeast fermentation will abruptly come to a halt and hard skin will form. The same would happen if proofed in a banneton. Don’t expect after 24h for them to wake up and start puffing up your dough pretending nothing’s happened. The dough will be half ‘dead’ by then!

Yes, I always bake straight out of the fridge.

My gut feeling Gary is that you’re pressing too hard on the science part here. If something didn’t work well for you, change it in your next bake. One thing/parameter at a time keeping track of what benefits or hurts the outcome, step by step.

Hope this helps a little.

Well said about the balance of art and science in bread making. I agree “Positive thinking” versus “hope this works” goes a long way towards making good bread. Thanks for sharing your bakes.

Don