So instead of baking this weekend I embarked on a science experiment currently in progress to find out if too much sugar starves yeast. This is something you occasionally hear and may have experienced proofing yeast before with too much sugar in the water mixture. Fortunately my eldest boy who is in Jr high has an experiment and got somewhat interested in the biology and chemistry and together we can up with a hypothesis that it's not really too much sugar but saturation we levels that prevent enough h20 to pass the yeast cell walls. As it turns out the cell must break sucrose into glucose and the funny thing is that splitting C12H22O11 into two molecules of C6H12O6 (sucrose and glucose respectively) leaves us 2 H and 1 O atom shy of achieving that goal or in other words, one water molecule.

So the hypothesis is that with overly saturated solutions of sucrose we are starving the cell of the requisite water and suppressing glucose metabolisms. We have a little setup currently where the same quantity of yeast has been introduced to a control solution, a saturated solution as well as a test solution that contains the same amount of yeast, 4 fold sugar and 4 fold water hoping to prove is the solution saturation is ideal regardless of how much sugar then equal yeast portions should produce equal gas output.

just thought it might be fun to to post and follow up with results (apologies if this is all basic known stuff but that's about the level of chem I remember)

thats definitely a worthwhile experiment - i never thought of it as an issue of hydration ratios i.e. sugar solution vs yeast l i always thought of it as sugar vs yeast . So i presume then that a well hydrated dough means you can you use more sugar relative to the yeast...makes total sense....

Posting the results soon ...

thinking of your 'sugar vs yeast' point above and the fact that we set out to disprove. After about 7 hours we saw that 'overfeeding' yeast with 4x the sugar and same water quantity did indeed stop yeast production. however our hypothesis specimen that also had 4x yeast but with same dilution as the control looked identical to the control - that really drove home the point that high sugar concentration is detrimental but, what's interesting is that over the next 24 hours the hypothesis specimen continued to produce gas whereas the control just sort of stopped. This suggest that if you have a good dilution that yeast actually seem to like it as there is more food to consume - ok that's it, yeast 101 dismissed !

Wow-that knowledge is really buried in my brain-4 yrs of high school chem and several years of college biology/microbiology. My memory tells me that the yeast membrane acted as a permeable membrane and the high concentration of sugar actually dehydrated them as the water left through their membrane in an attempt to dilute the surrounding solution to equalize it. But can that be right because I don't think they explode absorbing water if they are in a low concentration solution? On the other hand, there is a form of commercial baking yeast called "osmotolerant yeast" that performs much better in highly sweet doughs.

It will be interesting to hear about this.

You hear bakers talking about starving the cell of water and I believe that's exactly whats going on. No sure though about osmotolerant yeast and what they have done to it tobmakebitbfat resilient (the labs that is)

The hypothesis states that its not the amount of sugar to yeast but rather the concentration of sugar in solution that inhibits yeast metabolism - the experiment used 3 solutions of sugar with the same quantity of yeast which was 1g

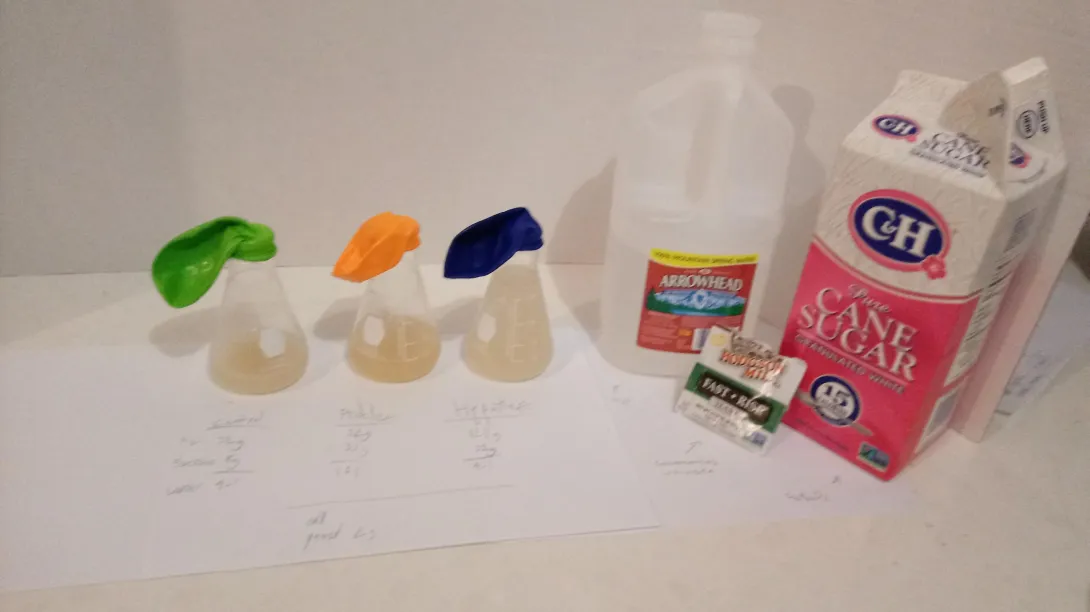

Using erlenmeyer flasks and colored balloons to trap CO2 as legends

- Control (solution at 4:1 water to sugar) 32ml H2O and 8g C12H22O11 or sucrose. Green balloon.

- Saturated (solution at 1:1) 32 ml H2O and 32g C12H22O11. Orange balloon.

- Diluted with ample sugar (4:1 ratio) 128ml H2O and 32g C12H22O11. Blue balloon.

The theory states that if solution is the problem and not the amount of sugar to yeast then our control should produce gas, our saturated solution should inhibit gas production and the diluted version that has the same high level of sugar should match the control since its dilution level matches the control. We chose colored balloons to indicate as noted above.

The results turned out pretty well as can be seen in the attached photo. The control and diluted show about equal gas production over 7 hrs of fermentation at 20c. It actually took 3 attemlts as we started with much lower sugar quantities and all 3 initially produced gas - it wasn't until we created basically simple syrup before yeast stopped metabolizing which is quite higher than I expected. The other good thing is it gives a hint to how much sugar it takes to really shut down the yeast and surprising how tolerant the yeast actually is. Had we have been more equipped I am sure we could start predicting degradation levels etc but all in all very educational !

Just for fun

C12H22O11 (sucrose) + H2O + INVERTASE -> C6H12O6 (Glucose) + C6H12O6 (Fructose) -> 4[C2H5OH + CO2] (Ethanol and CO2 Gas)

I feel like this almost -but not quite- makes sense to my old brain that never had much chemistry to start with! Am I understanding that heavy-on-the-sugar in a drier loaf will impede the yeast, but not in a wetter dough?

I wonder if there would be a variation in results if different types of sugars were used. Something like sucanat, coconut/date or other types of palm sugars, maybe even invert syrup. Also, are any of you aware of the type of yeast which is more adapted to the higher levels of sugar?

https://www.wildyeastblog.com/osmotolerant-yeast/

On another note, how would this phenomenon differ with something like sourdough or yeast water? The types of yeast and organisms can be different as well as the Ph with homemade yeast cultures, so are these type of yeast affected by sugar in the same ways?

I would think invert syrup im particular would be work well mainly because it's already some the job that is reserved for the invertase enzyme - ie split the sucrose to glucose and fructose. I'm not knowledgeable enough on other sugars so that would interesting to experiment or research. As for other yeast species especially those in sourdoughs who knows ! So much going on with lab and the fact that its a culture there are more variables to consider. Maybe this is an 8th grade project and maybe biology rather than chemistry !