A first and last ...

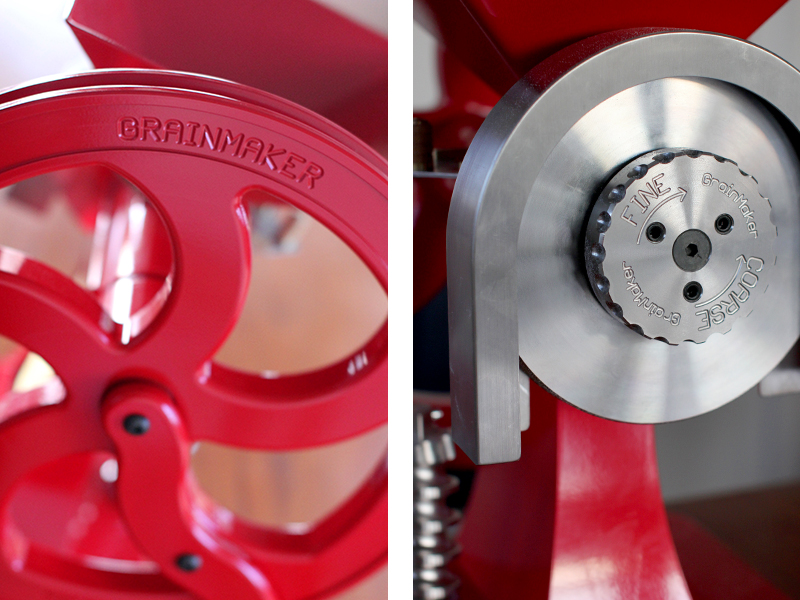

This is the first loaf I have baked using flour from my new Grainmaker mill—and the last loaf I will bake in this kitchen that I have been posting from for almost two years. We are moving house this weekend and amongst the piles of packed boxes and chaos I thought it might be a fitting end to try and find some time to bake a loaf and upload a post about it.

[url=http://www.flickr.com/photos/67856223@N06/9548590735/] [/url]

[/url]