(You can, if you wish, skip all my mutterings. The recipe is at the bottom.)

My little Welsh grandmother was a gentle soul with streaks of stubbornness, impishness, and independence just below the surface. Born in Wales in the 1883 she sailed to America, with her coalminer father and her mother in 1894. By the time I knew her only her baking, and a light lilt in her speech hinted her origins; she had become American, through and through.

My grandfather died the year I was born, leaving my grandmother a widow. She spent the rest of her life living with her oldest daughter, Alice, also a widow due a horse drawn milk wagon falling on her husband, who was the duo’s bread winner. She held a good paying job. They lived comfortably, and quietly—until the grandchildren started to arrive. I was the third grandchild born amid six—two each among her other three children—and the first boy, fathered by her oldest son: oldest son of the oldest son. I came to learn that gave me important status in the Welsh culture that shaped grandma. She spoiled me rotten. Childless, Alice spoiled all of us.

Grandma was grateful to Alice for providing hearth and home, but refused Alice’s money to pay for gifts for her grandchildren. To earn money—a necessary tool to spoil grandchildren—she marketed her crafts. She tatted doilies; crocheted doll clothes; made stuffed dolls from working men’s tall, white socks; and she baked. The Third Welsh Congregational Church's white elephant and bake sales were her initial outlet store. By the time I could drive, she had nearly twenty loyal customers throughout the city. I was her delivery boy. Every Thursday, after school, I drove to Grandma’s house; loaded the family car with bagged, wax paper wrapped loaves—white and whole wheat—and drove her route. The smell leaking from the bags was my teen year’s drug of choice. I got high sniffing bread once a week.

Her prices, for the times, were expensive: fifty cents a loaf, but no customer complained. Wonder Bread’s predecessors sold for about eighteen cents a loaf in the stores. Despite the city’s highly immigrant population, European style breads were missing from the shelves of local bakeries. The phrase “artisan breads” wouldn’t be invented for fifty years.

In the month before Christmas, and only for “special” customers, she also made Welsh cookies—$1 dollar a dozen.

A brief tutorial: England and Wales had many mines: tin, lead, and coal, Miners worked hard, and needed energy to keep going. Mine owners were cruel despoilers. (Ref: watch How Green was my Valley 20th Century Fox, 1941—I find fictional references contain much more imaginative examples than those in nonfictional references.) Miners carried there lunch and snacks into the depths of the mines, and ate lunch on the job.

Tin mines are especially hazardous, tin ores contain arsenic compounds. Tin miners can’t risk touching their food with their dirty hands. To the rescue, the Cornish pastie: a pot roast en croute; eat the innards; throw away the crust. Live for another day of mining.

Coal is mostly carbon, just like we are. A little coal dust never hurt anyone (discounting Black Lung), right? Welsh coal miners carried Welsh cakes in their pockets; loaded with lard (more about lard, later), and butter, and sugar the cakes were packed with energy almost as dense as that in the dynamite used to harvest the coal: energy to mine more coal, or run like the devil when the roof starts falling (see above reference.).

I haven’t the slightest idea what lead miners ate in lead mines (can’t find a reference.).

Welsh Cakes: the recipe.

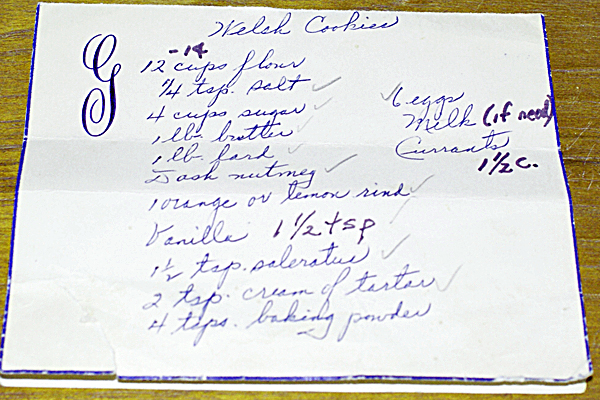

The original recipe, complements of Aunt Alice. Grandma’s eyesight had failed by the time I asked for the recipe. Alice only sent the ingredients. I was flattered she had assumed I knew how to assemble them. The inelegant, heavy-handed printing is my notations. Trivia question: What the hell is saleratus? (Answer below.)

Ingredients

12 cups all-purpose flour (51 oz.) (More may be needed to achieve a stiff dough)

¼ tsp. Salt (if you use unsalted butter increase to 1-¼ tsp.)

4 cups sugar

1 lb. Butter

1 lb. Lard

6 eggs

½ tsp. nutmeg (I like the flavor of nutmeg, reduce to a ¼ tsp. if you choose, but don’t leave it out entirely)

1 lemon zest (Grandma always used lemon, orange doesn’t have it for me.)

2 tsp. Vanilla

1-½ tsp. baking soda (answer to Trivia question.)

2 tsp. cream of tarter

4 tsp. baking powder

1-½ cup currants (I substituted dried cranberries once, delicious but not tradition!)

Directions

Let’s first get the lard issue out of the way. I had coronary artery bypass surgery twenty years ago. Subsequently, I tried, over and over again, to reduce the fat in this recipe. I failed. Every attempt was a disaster. Then I tried substituting butter for the lard; better, but the texture was heavy. Like good pie dough's flakiness, this recipe benefits from the lard. Trust me; don’t waste your time experimenting. Besides, I think you should really challenge your Lipitor once in a while to keep it at peak performance. Incidentally, most supermarkets carry lard; you will find it where Crisco is displayed, not in the refrigerator section.

Cream the butter, lard and sugar until light and fluffy, add the eggs one at a time, nutmeg, lemon zest, and vanilla and combine thoroughly.

Mix the flour, salt and other dry ingredients; whisk to distribute evenly.

Combine the wet and dry ingredients. Add the currants. Work gently, only until a homogenous, stiff dough is formed; don’t overwork it.

Note: the original recipe calls for milk if the dough feels too stiff. That’s never happened for me. I always need to add a bit more flour to achieve the desired stiffness.

If you are making the whole recipe—I never make less than a half recipe—divide the dough into four equal pieces, roll into balls, and flatten into 1 inch thick discs (just like pie dough). Wrap in plastic wrap and refrigerate for at least three hours. (I sometimes leave it overnight.)

Work with one disc of dough at a time, leaving the others in the refrigerator. Roll out evenly to ¼ inch thickness on a lightly floured board. Cut out cookie size circles. (I use a 2-3/8 inch diameter biscuit cutter; Grandma used a Welch’s grape jelly glass)

Preheat your griddle. I use an electric, non-stick griddle, with the temperature control set to 350°F. For a stove top griddle, or a nonspecific heat knob equipped electric grill, you’ll just have to experiment. Start with medium. On a non-stick surface no oil is needed, and I highly recommend you use a very light coating (an oiled, paper towel wipe) on other surfaces only if needed. (I make pancakes on a seasoned cast iron griddle with no oil, and no sticking. I think I did the same with Welsh cakes in long past years.)

Fry until deep golden brown on both sides, turning once. Cool thoroughly. Expect a light, almost flaky texture, and a clean taste with hints of lemon and nutmeg.

This recipe makes about 10 dozen. The cakes freeze very well.

One final experiment NOT to try: Do not try baking Welsh cakes; even my dogs wouldn’t eat them!

Sorry, I don't have a picture of the final product. I'll post one in December.

Update:

Here is the promised pictures. We started our annual Christmas cookie bake today.

Rolled out, and cut.

Six or seven minutes on a side at 350°F. An electric grill sure beats the top of a wood-fired stove Grandma learned on.

Ready for Christmas.

David G.